Programming Paradigms

August 11, 2024

Ideas and Code

Writing code is a never-ending battle to translate abstract ideas into formal instructions. This translation is lossy by nature: by making our ideas concrete, we are forced to face their inherent complexity and the bewilderingly large set of ways to arrange their inner-workings1.

Programming is ultimately about coping with this complexity, often by imposing extra constraints, for example:

- Paradigms

- Programming Language Syntax

- Style/Structural Conventions

- Idioms

- Design Patterns

The goal is for these rules to narrow the scope of possible translations, reducing the likelihood of out-of-control complexity. However, the rules aren’t perfect, and they almost always leave something to be desired. This framework for expression of ideas is all too often at odds with the ideas themselves.

This post attempts to dissect why this is and explore strategies for writing code that more closely mirrors the ideas that generated it.

The Translation Process

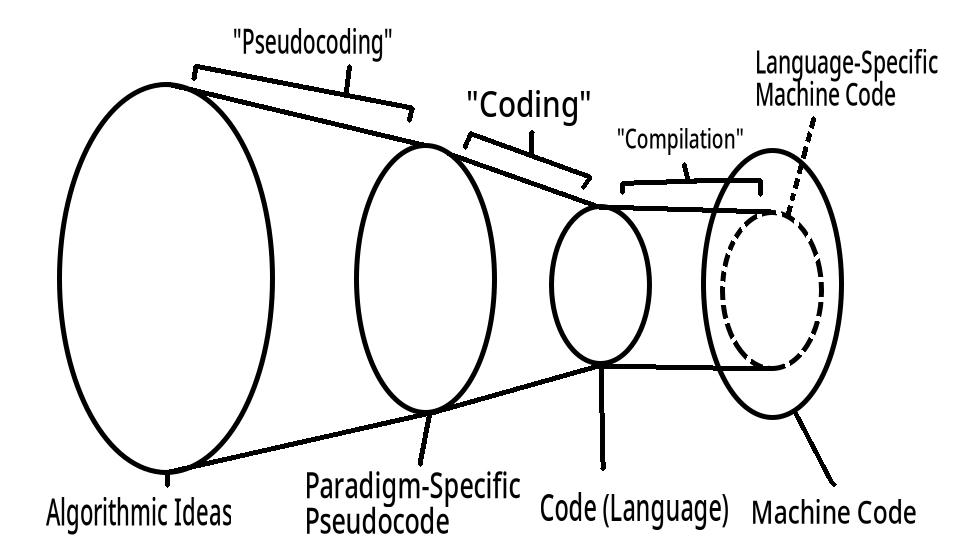

Despite what the hacker movies2 might imply, coding is a tricker process than just typing up a desired program3. I mentioned above that coding is a translation (of ideas to code), but the word “translation” doesn’t do it justice. Coding is more like translating feelings to music than translating English to Spanish. Ideas and code (like feelings and music) are not of the same fabric. Conversion between the two is rarely straight-forward4.

Nevertheless, there seems to be a hint of common structure to the way we conceptualize programming. Pseudocode is an aid for communicating ideas and conceptualizing code before it’s instantiated. Though it’s often used as an external tool, It can also describe5 an internal step of translation: in the process of making code from ideas, our minds first convert the ideas to some sort of mental pseudocode6, then convert that pseudocode into mental code7, which can then be written down8.

This pseudocode step is interesting because (by my definition) pseudocode is influenced by paradigms, where ideas are not.

My Definitions9

Algorithmic10 Ideas are loose conceptualizations of processes, removed from concrete instantiation. They’re like intuitive function signatures. You can think of them as “mathematical ideas” (though math is sometimes too eager in describing the process). They’re also (for the purpose of this post) assumed to be atomic enough that the translation to pseudocode is primarily a matter of paradigm (and not of other types of organization (i.e. code organization/ architecture11)), yet high-level enough that they catch the majority of the paradigm’s influence12. Examples: (“find the shortest path”; “reverse the list”; “find the topological ordering”; “trim the string”)13.

Paradigms are lenses in which algorithmic ideas are solidified into describable processes. They map14 ideas to pseudocode.

(Programming) Languages are higher-level representations of machine code. By definition (they produce runnable code), language code must be isomorphic to machine code, so languages are higher-level extensions of machine code. Despite this, they play an important role, because they (1) constrain the possible machine code translations, and (2) constrain the way we think about machine code formulation. More on this later.

An Example Translation

Consider the Trapping Rain Water problem15. We can solve this via two different paradigms: imperative and functional.

First, we develop an algorithmic idea that solves the problem.

If a column traps any rain water, there must be a higher column on the left and on the right.

If such columns exist, then the amount of rain water trapped is: min(left_height - col_height, right_height - col_height)

Then we write pseudocode (according to the paradigm).

Imperative:

Key Observations:

- If we place two pointers on both ends of the array,

we can maintain the invariant that each pointer points to the highest column on its respective side

- (highest == there exists no higher outer column != there exists no equal outer column)

- This is obviously true at the beginning (since the pointers start at the ends, and there are no columns beyond those)

- We can maintain this invariant so long as we only move pointers inward to nondecreasing values

- If we repeatedly "advance" the pointer with the lowest value to the next inward column with a value no less than it,

all columns "advanced over" will trap max(0, moving_pointer_height - col_height) units of water

- Since we are moving the lower pointer inward, and the opposite pointer is higher,

we know that all advanced-over columns can safely hold at least (moving-pointer_height - col_height)

- Since (by the first invariant) the moving pointer is the highest on its side,

and (by the definition of advancing) it's higher than all advanced-over columns,

all advanced-over columns can't hold any more than (moving_pointer_height - col_height)

- By doing this until the pointer converge, we will advance over all columns that trap any water

- Therefore the sum of all advanced-over columns is the total trapped water

we know that all advanced-over columns are

Steps:

- Initialize the two pointer and the total

- Loop until convergence

- Advance the lower (or arbitrary, if equal) of the two pointers,

adding the trapped water of the advanced-over columns to the total

- The result is the total

Functional:

Key Observations:

- If we can group together the (left_height, right_height, col_height) for each column,

then we can derive how much rain water each column traps

- left_height and right_height can be computed via "scan"s

- The grouping can be done via "zip"

Steps:

- Compute the left_height and right_height for each cell by using a max-scan on the input and the reversed input (respectively)

- Compute the amount of trapped rain water for each cell by zipping col_height (the input), left_height, and right_height

- Sum the trapped rain water across all columns for the result

Then code.

Imperative (C++):

int trap(vector<int>& height) {

int total = 0;

int left = 0;

int right = height.size() - 1;

while(left < right - 1) {

if(height[left] <= height[right]) { // advance left

int i = left;

while(height[++i] < height[left]) total += height[left] - height[i];

left = i;

} else { // advance right

int i = right;

while(height[--i] < height[right]) total += height[right] - height[i];

right = i;

}

}

return total;

}

Functional (Haskell):

trap :: [Int] -> Int

trap [] = 0

trap height = sum $ zipWith (-) (zipWith min left right) height

where left = scanl max (head height) (tail height)

right = scanr max (last height) (init height)

Transcending Paradigms

Clearly, the above problem is better fitted16 for the functional approach. The imperative approach introduces a load of unnecessary complexity, and relies on invariants and edge-cases that are hard to follow. The functional approach is so much more straight-forward that the pseudocode has room to discuss more mundane implementation details rather than justify algorithmic decisions17.

This is reasonable evidence to conclude that this algorithmic idea is less lossily translated via the functional paradigm.

This isn’t true for all problems, though. There are other examples where problems are better served by the imperative paradigm, or something else entirely.

This leads to the following questions:

- How do we cope with a languages (that must be used) that don’t coincide with the desired paradigm?

- How do we design languages that nicely allow multiple paradigms?

(1) happens a lot when working in a large or legacy codebase, where tooling (namely languages) is already set up, and static across all problems. You might be forced to code in some language (C++) to solve a problem (Trapping Rain Water) better suited for some other language (Haskell), which better matches the ideal translation-paradigm (Functional).

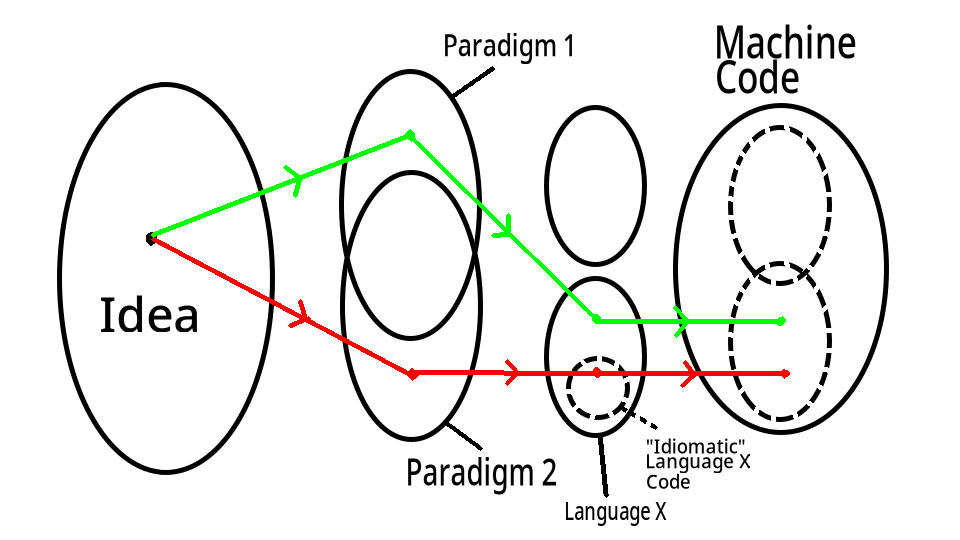

One solution is just to code in C++ with functional style (“as if it were Haskell”, in a way). In other words, use functional pseudocode, but translate it into C++. I’ll call this technique Alternate Paradigm Mapping. The below figure illustrates this, where

- “Language X” = C++

- “Paradigm 1” = Functional

- “Paradigm 2” = Imperative

The figure shows how the case where the resulting code isn’t idiomatic. This isn’t necessarily true, though, as the programmer can decide to stray farther from the translation-paradigm to make the code more idiomatic.

The below is a C++ solution to Trapping Rain Water, written using the functional approach. It is (relatively) idiomatic18.

int trap(vector<int>& height) {

int N = height.size();

vector<int> left(N), right(N); // largest on left/right respectively

for(int i = 1; i < height.size(); i++) left[i] = max(left[i - 1], height[i - 1]);

for(int i = N - 2; i >= 0; i--) right[i] = max(right[i + 1], height[i + 1]);

int result = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < N; i++) result += max(0, min(left[i], right[i]) - height[i]);

return result;

}

(2) is (yet another) question deserving of its own post, but here I will only note that almost all popular modern languages attempt to be “multi paradigm”, or at least provide some native features to facilitate the usage of more than one paradigm.

But even if a language “supports” a paradigm, and the programmer “understands” those features, the programmer won’t necessarily successfully accomplish alternate-paradigm-mapping (or even know when to try) if they don’t have a strong grasp on the paradigm they’re trying to pseudocode with.

Grasping Paradigms: Galaxy-Brain Languages

You can’t simply “learn a paradigm”20 by studying the concepts behind it. You instead must mold the mental circuits (the mappings from ideas to pseudocode) like any other skill: by repeated feedback. This is done through coding.

It’s hard to learn paradigms through multi-paradigm languages because they aren’t stubborn enough. You map your idea to pseudocode in the same way you always do, and since the multi-paradigm language is relatively flexible, you’re able to translate that pseudocode directly into the language. You might learn a new language feature or two, but the mapping from idea to pseudocode isn’t forced to change.

Instead consider a “galaxy-brain language”: a language that steadfastly adheres to a single paradigm. When you use such a language, you translate the idea into pseudocode, and you try to translate that pseudocode into code, but you fail, because the pseudocode is too different from the target-language’s code. You battle with the code until you find a way that works, then you repeat the process over again. Do this over time, and you develop an understanding of the paradigm. It’s like learning to code again.

(Galaxy-Brain languages (from Conor Hoekstra’s Blog))21:

- ALGOL: (1958) The original imperative programming language

- Forth: (1970) The original stack-based programming language

- Lisp: (1958) The original Lisp

- Haskell: (1990) A pure functional language

- Smalltalk: (1972) The original object-oriented programming language

- Erlang: (1986) The original actor-based/concurrent programming language

- Prolog: (1972) The original logic programming language

- APL: (1966) The original array programming language

This image is often used jokingly, but learning a new galaxy-brain language really does expand mental connections, so it isn’t terribly inaccurate.

The Résumé Languages

If you understand the paradigms behind ALGOL and Smalltalk (imperative and OOP, respectively), you can code in virtually any modern multi-paradigm language. 95% of languages I’ve seen on Résumés fall into this category.

Everyone and their mother can code in these langauges:

- Java/C++

- Python

- JavaScript/TypeScript

And at least a few of the below:

- C

- C#

- Go

- Matlab

- Rust

- Swift

- Kotlin

- Ruby

- Lua

Paradigms (and diversity of pseudocoding) are not discrete: translation ability is way more nuanced then simply “count of known paradigms”22, and languages don’t have a one-to-one correspondence with paradigms. There is some value to learning more than one of these languages, but it’s folly to assume that knowing several of these is the same as knowing several paradigms (or galaxy-brain languages). Knowing many of these languages primarily represents experience with tooling, while knowing many paradigms represents mastery and versatility of coding.

One Paradigm Is Sub-Ideal

As a programmer becomes comfortable with a single23 translation method (without context of any others), it becomes harder for them to draw the line between the ideas and their translations.

This might be harder to see in more moderate cases, but it’s clearly true at the extremes:

- The 30-year COBOL developer who doesn’t know what JavaScript is24

- The FP enthusiast who swears by Haskell and scorns all industrial programming and SoyDevery

- The astronomer/scientist who solely uses Python for their studies

- The SoyDev who refuses to use a language that doesn’t end in the word “script”

For single-paradigm devs, abstract thought is synonymous with coding25. What happens when the solution they’re trying to write is better expressed in another paradigm26?

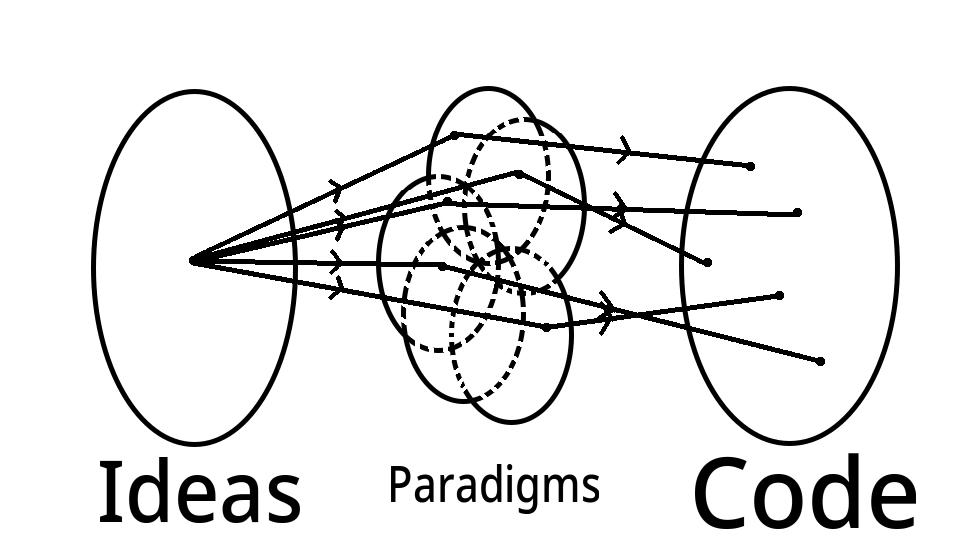

While most of us aren’t quite as polar as the above stereotypes, we have same weakness, just to a lesser degree. The fewer ways we know to express code, the more rigid our ideation of code becomes. Conversely, the more paradigms22 we know, the more flexibility we have in problem-solving.

Building the Toolbelt

The more paradigms you have at your disposal, the more ways you’ll be able to code the same idea (even in a single language). Of these ways, you are free to choose the most exact translation of the original idea, leading to code that is more simple, readable, and maintainable.

Expanding your toolbelt of paradigms will therefore improve the quality of the code you write, improving the development experience of you and everybody who interacts with your code.

For a more practical exploration of why this is and how we can best deal with it, see my post on the necessity of hacking. ↩︎

This scene from “The Social Network” is a good example of this. Mark isn’t actually “coding” (developing software) in this scene, but the general idea holds. ↩︎

The exception to this is when sufficient intuition is developed. Intuition can effectively create a memoization of mappings from ideas to code. This why the movie isn’t unrealistic (apparently it’s pretty accurate). Furthermore, the coolness of the movie implies the coolness of intuition. ↩︎

Though one translation may seem straight-forward to one individual, there is undoubtedly another who would translate it in an entirely different way (straight-forward = injective (one-to-one)). Some ideas are just flat-out hard to instantiate as code (straight-forward = total) ↩︎

I would argue that pseudocode comes from externalizing the mental translation step, not the other way around. ↩︎

In a very informal sense: the “mental pseudocode” is probably in some sort of “mental assembly language” (some arrangement of neuron signals, or whatever) that doesn’t directly represent the text of pseudocode (per se), but serves the same purpose. ↩︎

This probably happens unconsciously, and it might be (fully or partially) memoized via intuition (so can the pseudocode-to-code step). ↩︎

We’ll elide the mental-code-to-real-code step (which might be interesting in some ways, because “mental code” (as with “mental pseudocode”) likely doesn’t exactly match real code) because it’s tangential to this post’s main discussion. ↩︎

All definitions are within the context of this post, and don’t necessarily reflect the true “definition of the terms” (used by others, or by myself in other places). ↩︎

“Algorithm” is probably a bad term (since its definition might imply a “concrete process”), but I chose it because of its connotation of abstraction. ↩︎

High-level architectural design is beyond the scope of this discussion (and deserves its own post), but it could probably be described by a similar 3-step process (“idea -> intermediate -> concrete”) ↩︎

This model is lossy in that sense (paradigms influence the translation of problems into ideas too, and generally change the nature of mental computation). By simplifiying the definition of “paradigm”, we lose this nuance, but we gain the ability to reason more formally. ↩︎

These example mix functional ("[find/return]…") and imperative ("[do/modify]…") langauge; ideally, ideas would be described without any such implications (as they, by definition, should have minimal linkage to implementation). This further shows how ideas lose their freedom from paradigms when they’re instantiated in any way. ↩︎

Paradigms can be viewed as mappings (by this definition), and also (isomorphicly) as definitions of pseudocode flavors (which is the representation I chose for the diagram; I chose it because “pseudocoding” is more intuitive than “applying the paradigm mapping to produce pseudocode” or the like). ↩︎

I chose this problem (and these solutions) because the differences between the two pseudocodes illustrates my point well. While I think it’s realistic, you might consider the imperative solution a little eggagerated (the two-pointer solution might not be the most natural jump from the idea). In most cases, the differences are more subtle. ↩︎

Technically, the functional approach is asymptotically less memory-efficient, but (in most cases), I’d argue that the safety and clarity provided by the functional approach far outweighs the benefits of memory-efficiency. ↩︎

This ties in with Miller’s Law that our working memory is finite. I discuss how this manifests and more ways to cope with it in my post on programming without fear. By choosing a paradigm that better matches the idea, we can avoid the unnecessary burden of mental computation and focus our attention on more fine-grained (or overarching) problems. ↩︎

Idiomatic with respect to the average Leetcode C++ solution: I highly doubt there’s an agreement on what constitutes idiomatic C++, even among its professional users. ↩︎

What’s really neat here is that, by looking at this C++, (unless you’re a FP nut) you probably wouldn’t notice that it was influenced by functional thinking. Learning a “fringe” paradigm (like functional) doesn’t just teach you to code in esoteric ways (Haskell), it also can be used to write “normal code” in subtly better ways. It “makes you a better programmer”. This isn’t just true in this (extreme) example: I notice little things like this all the time when programming in all different languages. ↩︎

This is either because (1) it’s exceedingly impractical to try to understand such a complex thing, or (2) because it simply isn’t possible to teach a way of thinking by describing it (and not exercising it). ↩︎

Note that each language on this list is a representative from a paradigm. You could make a lot of substitutions (C serves just as well as ALGOL, for instance). The only real criteria for “galaxy-brain” is that the language forces you to think differently than you did before. ↩︎

There aren’t even that many widely adopted “paradigms” (that have well-known names), and the bounds and definitions of a paradigm are blurred. You can instead imagine it as a spectrum of diversity of thought. ↩︎ ↩︎

Or a small few ↩︎

I drafted this before I met people who actually fit this description. Now I feel a little guilty, because it’s so accurate that it might be seen as an insult. Let it be known that I mean no offense to anybody who falls into these categories. Having single-mindedness (when it comes to development) doesn’t necessarily make a person bad at serving their respective role. But it can definitely be detrimental in an environment that requires flexibility and nuanced perspective (most non-legacy development). ↩︎

The ideas-to-pseudocode-to-code pipeline becomes so intuitive (so highly memoized) that it’s fused into a mapping that’s wicked to pull apart. ↩︎

They greatly lose efficiency, flexibility, and concision. Here’s an example. ↩︎