Pushing Random Buttons

April 1, 2024

Before I discovered programming, a lot of my time around computers was spent becoming intimately familiar with the software I used on a daily basis. I became a master of Microsoft Power-Point transitions, keyboard shortcuts of all kinds, and I had a particularly curious habit of exploring the Windows1 and iOS settings menus, where I would toggle every setting and observe its impact on the system.

My approach towards understanding software generally fell into the paradigm of “push random buttons”: I was completely uncalculated and unmethodical. I aimlessly showered my computer with clicks in every direction, exploring the boundaries of what it could do, not unlike how toddlers misbehave to discover the boundaries of society.

The amazing part is that this works. I rapidly gained a dictionary-like knowledge of and intuition for high-level user interfaces, leaving my computer relatively unscathed, aside from a few sketchily downloaded programs and a few near-deletions of System32.

Software is unique in this sense: you can’t learn to fly a plane in this way: pilots couldn’t fathom that convenience: they’re forced to painstakingly study the behaviors and relationships between the buttons in a cockpit before they even lay their fingers on them.

The ability to use this method makes it possible to learn to use and write software incredibly quickly and effectively. The downside is that, because it is so effective, there’s much less of a need for resources that spell out the things that can be learned through the method, and, as a result, it has become a necessary skill in the growing and changing world of software development.

Necessity

Here’s a compelling quote from Gerald Jay Sussman (one of the writers of SICP), from this video, where he’s commenting on why MIT no longer teaches SICP:

“It seemed to be that the change in the engineering type that was needed in the future no longer [put] so much pressure on understanding how a bigger thing is made out of smaller things by combining the parts and understanding from the pieces how the parts work… [it had shifted] to one that is more like science: you grab this piece of library, and you write programs that poke at it to see what it does, and you say ‘can I tweak it to do the thing I want?’ It’s what we do now, a lot.”

Software today is not modular in the way it was several decades ago: in order to create good modern software, you must be willing to stand on the shoulders of giants and make use of the sea of existing tools and libraries, which no individual can ever hope of totally understanding.

Software developers must learn to use sparsely documented APIs and open-source projects. Even the most well documented libraries don’t spell out exactly how they should be used. The only way to figure them out is to incrementally poke at them in different ways until the outcome is desirable.

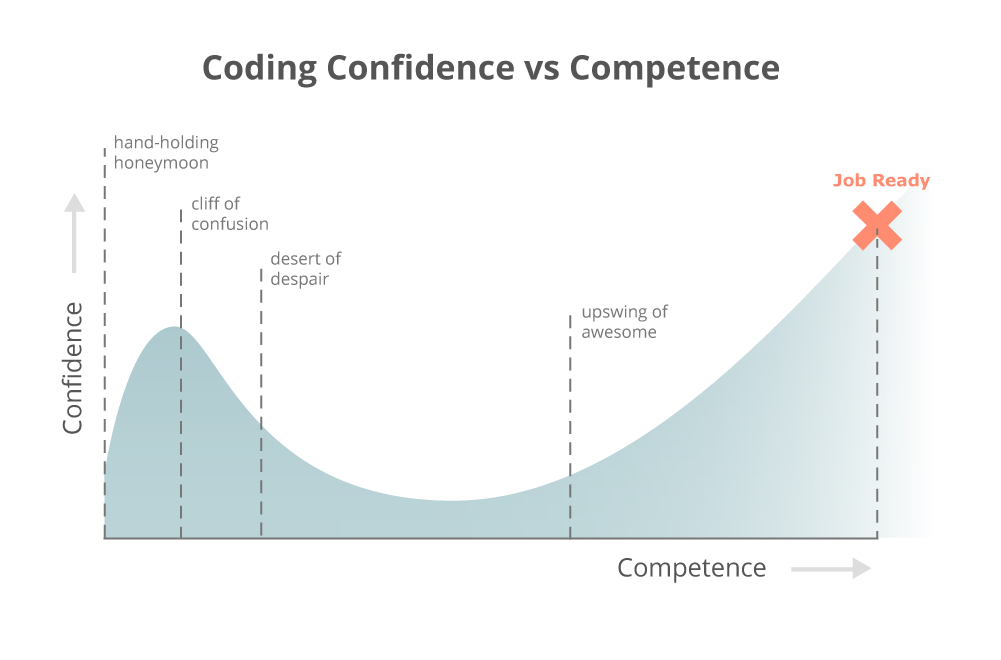

Navigating the Desert of Despair

“The Desert of Despair is the long and lonely journey through a pathless landscape where every new direction seems correct but you’re frequently going in circles and you’re starving for the resources to get you through it.”

(from this blog post)

I think that a major reason that the Desert of Despair exists is the difficulty of becoming comfortable with using the push-random-buttons approach towards learning (especially when it comes to novel technologies and tools).

Resources for intermediate programmers are scarce: I suspect that this has a lot to do with the inherent difficulty and complexity in adequately describing ever-changing tools/libraries (which seem to be the primary focus in this stage of learning 2); such tools/libraries are often poorly documented and menacing in size, which makes learning them pretty demoralizing until their unknowability is accepted, and the programmer shifts to (and becomes effective at) the button-pushing approach.

Feedback Loops

Adopting this approach is easier said than done. It’s a lot harder to poke at a million-line codebase than it is to press a button on Microsoft Word’s ribbon. This barrier is primarily mental, and the best way to overcome it is to repeatedly prove its fragility. This means repeatedly succeeding in achieving the intended outcomes, despite perceived difficulty.

The fastest (and most exciting) way to do this is to maximize the rate at which buttons are found, and their impacts observed (i.e. tightening the information feedback loop).

This is an area where I could greatly use advice, but here are a few strategies I’ve found to be effective.

- Make maximal use of the available code-exploration tools

- IDEs

- Git / Github

- Linters

- Use LLMs (GPT) as a quick initial effort, but give up quickly if they lead you astray (especially when it comes to specific APIs or especially technical problems)

- Strive to accept incomplete understandings

- Aim for a minimum-viable-implementation before sweating the small stuff

Windows has a wide variety of settings menus, many of which are highly specialized and clearly written in a previous decade. The menus I can immediately recall: the vanilla settings menu, control panel (and its many submenus), device manager, event scheduler, and the elusive registry editor. ↩︎

The early stages focus on programming fundamentals, and the later stages focus on high-level architectural ideas and low-level nuances. ↩︎