The Breadth-Depth Phase Shift

May 5, 2024

Learning computer science is a lot like forming an n-dimensional1 snowball.

- Beginning is tough, because you must start from nothing; the snowball begins as a tiny clump, and is prone to crumbling.

- Eventually, you reach a critical mass, and the snowball can be rolled along the ground, and its own weight helps it effortlessly pick up snow and build upon itself.

- The snowball’s mass grows until it becomes so large and heavy that rolling takes great effort, and is no longer a viable strategy.

I think (1) and (2) are pretty well-known and agreed upon; starting with programming is pretty tricky, but over time momentum gets built up, and there’s a foundation to build on top of.

The plateau in (3) is a little less obvious, but a lot more interesting.

Breadth and Depth

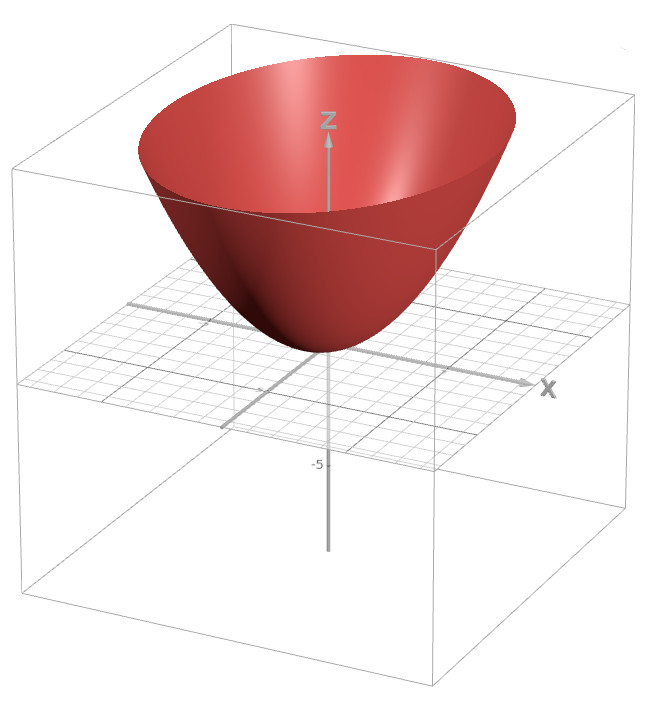

The snowball analogy isn’t perfectly accurate: the difficulty of pushing the snowball comes from the weight of the snow, but the difficulty of expanding the n-dimensional-cs-knowledge-sphere comes from the impossibility to keep up with the increasingly large surface area (which grows polynomially2 as the radius grows linearly). So, though it’s possible to keep learning the same overall volume of material, the expansion of the frontier of knowledge will inevitably slow.

It naturally follows that, if you want to acquire mastery in CS, you must accept specialization, and shift towards expanding your frontier in a much narrower direction.

This is precisely what happens in both industry and academia: your skills are directed and tuned in to pursue depth in a particular field. In industry, it’s usually a particular set of tools, part of the tech-stack, or area of application; in academia, it’s a subject area.

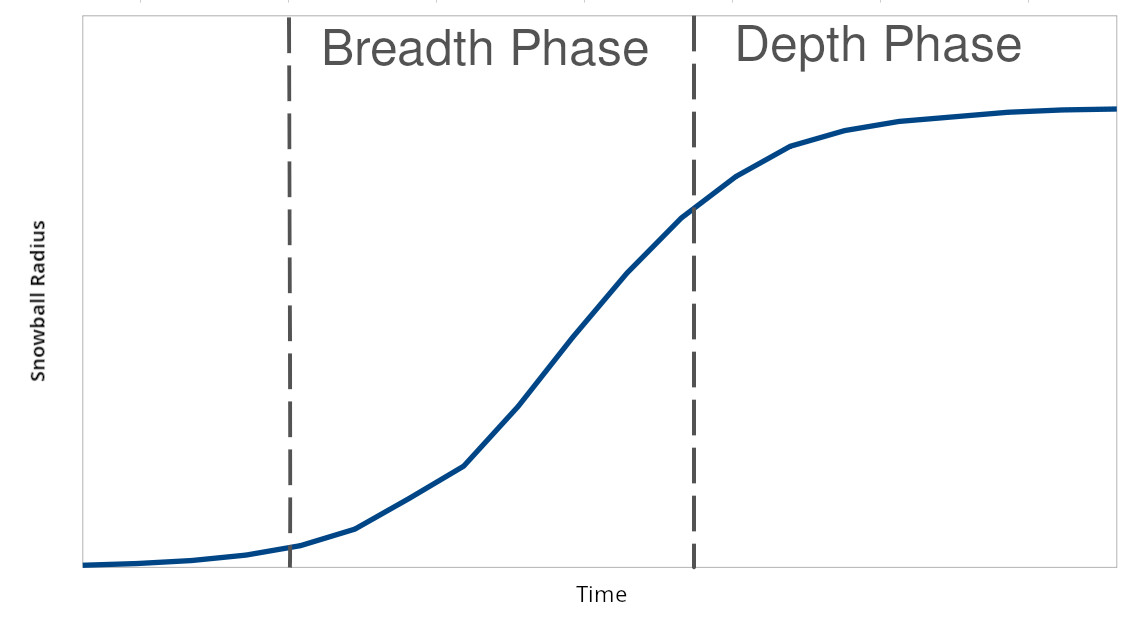

The above is a highly scientific plotting of snowball radius over time. An interesting thing to note here is that the vast majority of radius growth happens in the breadth phase, very early on in a programmer’s journey (say, 1-5 years of learning). The chart isn’t to scale (or is cut off on the right), but the depth phase expands indefinitely outward: even though expertise greatly increases over the years, breadth doesn’t expand too much beyond that initial foundation.

Manifestation

All of this seems relatively obvious when it’s pointed out, but it can be easy to ignore when you’re up close to the painting (when you’re so consumed in your own learning that it’s hard to objectively analyze and adjust your trajectory). Furthermore, this phase-shift demands a change in strategy: when you’re in the breadth phase, practically any pursuit of knowledge will end up expanding the frontier in many directions, simply because the dimensions are much more interconnected near the origin. It’s easy to begin to expect success from these pursuits, then lose direction when they become less effective as the frontier grows.

For example, you might write a lot of miscellaneous programs3 when first learning to code, but as you improve, the programs get larger and larger, and soon, every program you write takes weeks (or months) to complete, yet, because those programs aren’t very directed, you gain less and less from them (and your time is less effective)4.

This example elucidates more nuance in this equation: the increasing-surface-area isn’t the only reason projects increase in difficulty over time. It’s also natural for programmers to pursue larger goals as they build their skills, and larger goals usually imply bigger and more complex programs (which take way more time). Not only does the frontier’s size balloon as it expands, but the difficulty of expanding the frontier at any given point is harder as that point moves away from the origin (as the topics becomes more advanced).

The below represents the difficulty of frontier-expansion (the z-axis) with respect to the area of the frontier being expanded (the x and y axes).

So What?

If you find yourself in situations like this, pushing incessantly on your snowball, yet making little ground, then it might be a good idea to narrow your focus5. It’s better to avoid fighting against nature, to understand your limitations, and work within their bounds. This is the most efficient and rewarding way forward.

The dimensions are all of the conceptual categories to learn. For a clearer visual, you might imagine doing some dimensionality reduction, bringing the CS snowball to, say, 3 dimensions: math, low-level (bits + hardware), and button pushing (libraries, languages, tools, etc.). ↩︎

I think: my intuition for higher-dimensional geometry isn’t strong, and I don’t intend for this to be a math post). Perhaps it’s exponential if the number of dimensions is variable. ↩︎

The same applies for solving drills (e.g. leetcode), or reading textbooks/articles at random. ↩︎

This happened to me, and it took me a long time to realize it. ↩︎

This doesn’t imply making a long-term commitment towards a specific area of study: focus can be rapidly shifted. It’s also possible (and ideal) to still go for “breadth”, but in a much more shallow way (in a limited arc of the frontier). For example, shifting from an overall generic focus to a focus in the realm of databases, or in development tooling. ↩︎