Types and Programming Languages

October 19, 2024

“Types and Programming Languages” (T&PLs) is a relatively-esoteric1 textbook about type theory. The professor2 of my college PLs class3 has an old webpage that recommends this book:

If you are serious about programming languages Benjamin Pierce’s Types and Programming Languages is a must.

This intrigued me, of course4, but it also appealed to my ego. Not only was it an interesting read, it was a must (if I was to consider myself serious about PLs).

Thus I began to romanticize the idea of reading this book, and it crept its way up my priorities.

The View From the Base (Intros, Motivation)

Reading a textbook is like climbing up a mountain. The author is your guide/mentor5. Before the climb begins (in the introduction of the textbook), the author (a seasoned climber) gestures cinematically towards the peak of the mountain, and waxes elegant about how grand the summit is, and how your climbing it is uniquely important in your career as a climber and adventurer.

The author/guide is a master of rhetoric, and they are contagiously convincing6. You are seduced.

But, tragically, your enthusiasm rarely remains for the duration of the trip, and the climb either grows too difficult7 or too mundane.

- category theory is an especially cool example of this; the intro alone convinces (despite my awareness of this likelihood)

The View

The introduction of T&PLs isn’t a perfect instantiation of the above generalization8, but it does have some poignant ideas that really struck a chord with me when I first read it.

The tension between conservativity and expressiveness is a fundamental fact of life in the design of type systems. The desire to allow more programs to be typed — by assigning more accurate types to their parts — is the main force driving research in the field. (3)

This idea presents the hope of having our cake and eating it too: we can dream of writing a program with the ease of Python and the safety of Haskell.

In practice, static typechecking exposes a surprisingly broad range of errors. Programmers working in richly typed languages often remark that their programs tend to “just work” once they pass the typechecker, much more often than they feel they have the right to expect. One possible explanation for this is that not only trivial mental slips (e.g., forgetting to convert a string to a number before taking its square root), but also deeper conceptual errors (e.g. neglecting a boundary condition in a complex case analysis, or confusing units in a scientific calculation), which often manifest as inconsistencies at the level of types. (4) 9

I’ve mentioned this feeling several times across a few different posts. I can’t understate the wonder of having your program “just work” after being conditioned to expect the opposite.

For example, a programmer who needs to change the definition of a complex data structure need not search by hand to find all the places in a large program where code involving this structure needs to be fixed. Once the declaration of the datatype has been changed, all of these sites become type-inconsistent, and they can be enumerated simply by running the compiler and examining where typechecking fails.

This reason alone (though it’s far from the only argument) makes me question the prevalence of dynamically typed systems.

The Real Contents

The first chapter (the introduction) got us all hyped up on practical applications, but now we turn to remaining 31 chapters, which primarily focus on theory. While I don’t dislike theory per se10, it was a bit of a let-down, because the intro had such compelling points that didn’t end up being elaborated upon11.

Takeways

There are a handful of big ideas throughout the book that I found compelling. None of them12 are groundbreaking in my eyes, but I don’t think that’s necessary for their sum to be of high utility. I’ll try to describe these ideas from a birds’ eye view.

Operational Semantics

The book’s chapters generally follow the format13:

- Give the motivation for a new language feature (something the current language can’t do)

- Describe the Operational Semantics for that feature

- Give some examples of how the feature is used

- Do some proofs about its properties

The book gives the following definition:

Operational semantics specifies the behavior of a programming language by defining a simple abstract machine for it. This machine is “abstract” in the sense that it uses the terms of the language as its machine code, rather than some low-level microprocessor instruction set. For simple languages, a state of the machine is just a term, and the machine’s behavior is defined by a transition function that, for each state, gives either the next state by performing a step of simplification on the term or declares that the machine has halted. The meaning of a term

tcan be taken to be the final state that the machine reaches when started withtat its initial state.

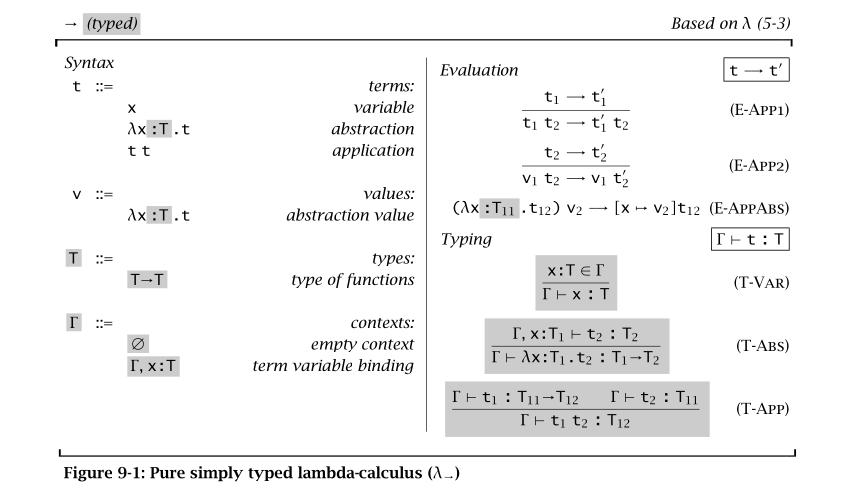

Here’s an example of the operational semantics for the simply typed lambda-calculus.

The horizontal bar is equivalent to the implication arrow (“assuming the top, the bottom follows”).

Don’t worry if the typing rules look a little hard to follow: the three-place typing relation ("Γ ⊢ t : T" means “the term t has type T under typing context Γ”) is a much easier to visually parse when you’re used to it.

I think this is a cool framework for describing programming languages, because it directly mirrors how we think about programs, and it’s minimally verbose (considering how formal it is), and it can be used to describe both evaluation and typing. It isn’t hard to imagine a non-academic dreaming up their own language feature, and writing out the operational semantics for it, then analyzing it the same way the book does14.

Lambda Calculus

The Lambda Calculus is the basis upon which every language feature in the book is described. This might not feel very practical if you don’t realize just how closely lambda calculus is related to mainstream languages.

It’s one thing to accept the lambda calculus as “the assembly language for functional programming”, or “an academic influence for functional languages”; it’s a whole different beast to see a (sizable15) subset of Java encoded in it, then build from the ground up, using similar operational semantics. Chapters 18 and 19 do just that.

From there, it’s not too hard to see that other, more-functional languages (like Haskell and OCaml) are clearly not too far from this highly-extended lambda calculus. This gives a new efficacy to the language features developed throughout the book, which no longer seem so far from practical implementation.

Subtyping

Subtyping gets a bad rap because of its association with inheritance (namely in Java), but there is no need for subtyping to require inheritance16.

This linkage between inheritance and subtyping puts a strong emphasis on thinking of subtypes as “the same as their supertypes, with some additional data/functionality tacked on”, instead of a “a subset of the supertype’s possible values”. These might be isomorphic from a theoretical perspective, but they yield significantly different outcomes when used practically.

It might be hard to see why these two perspectives are the same. Consider the classic example:

class Animal {

private int age;

public int getAge(int age) { return this.age; }

public void setAge(int age) { this.age = age; }

public String sound() { return "[indiscriminate noise]"; }

}

class Dog extends Animal {

private String breed;

public String getBreed() { return this.breed; }

public void setBreed(String breed) { this.breed = breed; }

public int ageInHumanYears() { return this.age * 7; }

@Override public String sound() { return "roof roof"; }

}

It’s very easy to see here, by construction, that Dog is “the same as” Animal, except that it also has a breed (which can be accessed and mutated), ageInHumanYears(), and it barks instead of making indiscriminate noises.

It isn’t quite so clear that the possible values of Dog is a subset of the possible values for Animal.

After all, Dog has more fields17 than Animal, and therefore there are more possible values for Dog, so how can the set of values for Dog be larger than the set of values for Animal, yet also be its subset?

To make this work, we have to view types deductively instead of constructively.

Instead of defining “the set of possible values18 for Animal” to be “the set of uniquely constructed Animals”, we define it as “every thing that happens to also be an Animal” (for this example thing refers to any Java object, and “happens to also be an Animal” means (loosely) that it has an age field).

By this definition, it’s much clearer to see that there are more possible values for Animal than for Dog, and that Dog’s possible values are a subset of those of Animal.

(loosely, avoiding Java's requirement of explicit declaration of subtyping and ignoring methods)

Animals that are not Dogs:

{age: 23}

{age: 38, shellColor: "green"}

{age: 3, numberOfLegs: 22, nocturnal: true}

Animals that are Dogs:

{age: 4, breed: "Mutt"}

{age: 5, breed: "German Shepherd", floppyEars: true}

{age: 84, breed: "Bichon Frisé", recentlyGroomed: false}

This deduction-based view can be quite useful in certain contexts (especially to primitive types, or those with more structural nuance than the average Java Object).

X <: Y <=> "X is a subtype of Y" <=> "every value of X is also a value of Y"

∀X. X <: Top (Top is defined as the supertype of all types: every value is a value of Top)

(in Java, Object is Top)

X <: Y => [X] <: [Y] (Lists)

... <: {x:T, y:G} <: {x:T} <: {} (Records)

...

Actually applying these sorts of subtyping rules to primitive types (or even user-defined types) might be a little questionable (because it makes type inference harder and potentially is too flexible where rigidity would be ideal), but there are certainly places where these ideas are applied practically, even if the programmer might not notice it. For example, Rust makes very heavy use of subtyping to make way for more advanced language features like lifetimes and dereferencing.

Recursion as a Fixpoint

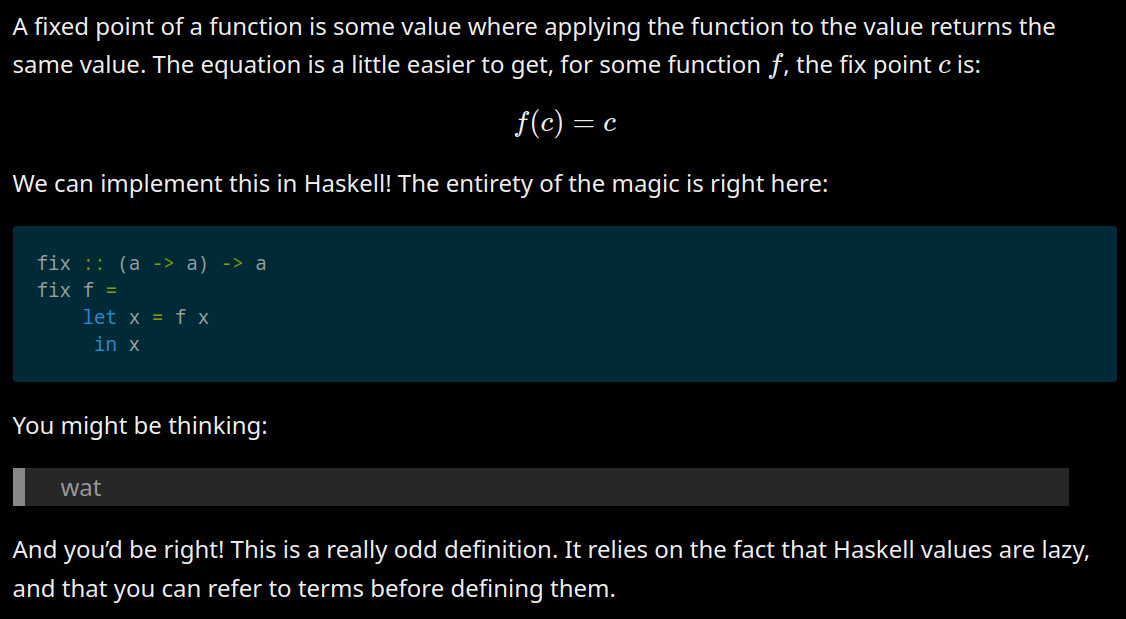

If you go deep enough into the Haskell rabbit hole, you’ll come across a function called fix.

Matt Parsons’ blog explains this relatably.

It turns out that fix is necessary for writing recursive functions in the Lambda Calculus19.

Haskell has built-in recursive functions, but it uses fix for more interesting constructions.

The idea is that you pass a function to fix, whose argument is used for recursive calls, and fix will “do the recursion for you”.

import Data.Function (fix)

fact :: (Int -> Int) -> (Int -> Int)

-- `f` is used to recurse

fact f = \n -> if n <= 0 then 0

else if n == 1 then 1

else f (n - 1) + f (n - 2)

factorial :: Int -> Int

factorial = fix fact

This took me a long time to really grasp, and this book helped me with it.

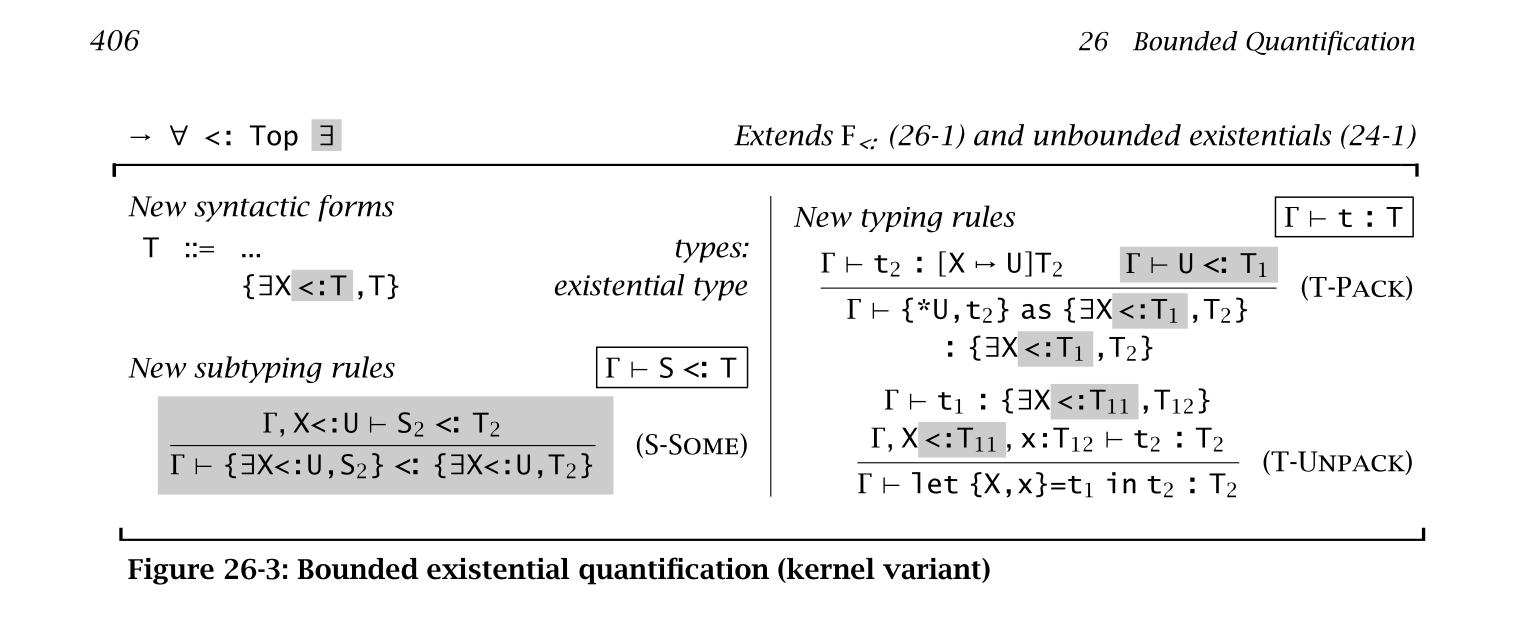

Types as arguments

“System F” is an extension of the Lambda Calculus that enables universal qualification by introducing a construct that takes a type as an argument and returns a value. The same lambda syntax is used.

For example, if we want a polymorphic identity function, of type:

∀A.A→A

It’s written like this:

λA. λx:A. x

This shows what’s going on behind the scenes with generics20 (say, in Haskell), and how types can effectively be viewed as arguments.

Fear of the Unknown

The process of reading this book reminded me of an occasion21 when I was in elementary school, when I saw my older brother working on his math homework. The symbols squiggled on the page looked unbelievably complex to my untrained eyes22. I remember thinking “wow, that looks so hard, I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to understand that”. But then, as the years went by, and I continued upward in math classes, I never ran into a new concept that seemed so unfathomable. Sure, it immediately wasn’t easy to pick up everything, but it was always doable. I kept waiting for that really hard concept – the one I wouldn’t be able to understand23 (the one I saw my brother working on) – to show up, but it never did.

When I paged through T&PLs before reading it, I felt much like young-me did when seeing my brother’s homework.

But when reading the book, no individual page was too difficult24.

The same was is for learning to code for the first time, learning APL and Haskell, and, for all I know, learning number theory and theoretical physics.

Very little is beyond your reach if you take small enough steps.

My usage of “esoteric” is relative. To the author (an academic), it’s high-level and perhaps even pragmatic (which the introduction says is a goal of the book). ↩︎

Kaiser Pister, star of this Primagen video ↩︎

Because I am interested in many ideas/studies surrounding the topic of PLs. But most software developers wouldn’t consider it practical (especially the proofs!). ↩︎

The author (or the words/instructions they left) is also the trail/path, depending on how you look at it. ↩︎

This isn’t to say it isn’t genuine: after all, they were passionate enough about this topic (climbing this particular mountain) to write a textbook about it (devote themselves to guiding others up). ↩︎

Guide: “just put your foot between those two rocks”. You: “Uuh… which rocks?”. Guide: [continues climbing]. ↩︎

Category Theory For Programmers by Bartosz Milewski has an introduction that fits this description even better than T&PL’s does. Despite my knowledge of this, I’m still excited to read it, and I’ll proabably write a post about it when I finish. ↩︎

The following sentence adds more nuance: “The strength of this effect depends on the expressiveness of the type system and on the programming task in question: programs that manipulate a variety of data structures (e.g., symbol processing applications such as compilers) offer more purchase for the typechecker than programs involving just a few simple types, such as numerical calculations in scientific applications… (4)”. It’s a good exercise to consider which camp the code you work on falls info. ↩︎

(it is a book on type theory, after all) ↩︎

For example, it would have been really cool to see some of these ideas applied in the guts of an advanced Haskell program, rather than just stopping at the proofs (it was hard to stay practically motivated). ↩︎

Nor are these ideas the ones I expected (or hoped) would be my takewaways. I came into reading this book with hopes of having big revelations about polymorphism and type-level functions, but the majority of the reading in those sections was either straight-forward or exceedingly esoteric (proof or meta-theory based). On the other hand, topics like subtyping and lambda calculus, which I wasn’t initially excited about, ended up being the most rich ideas in the book. ↩︎

There are also dedicated chapters for implementations (in OCaml), metatheory (proofs and math), and case-studies (applying the language features using more drawn-out examples). ↩︎

The odds that such a feature would be something that wasn’t already thought of by academics are slim, but it’s the possibility that counts. ↩︎

Large enough to feel usable (where the raw lambda calculus is definitely does not feel usable). ↩︎

Inheritance implies subtyping, but not the other way around. ↩︎

More precisely, the product of

Dog’s fields’ number-of-possible-values exceeds that ofAnimal’s. ↩︎Forgive my imprecise verbiage here: I don’t have any technical reason for saying “all possible values” rather than “all values” or “all instantiations”, or etc. ↩︎

The lambda-calculus-definition of

fix(fix = λf. (λx. f (λy. x x y)) (λx. f (λy. x x y))) is arguably more wat-inducing than Haskell’s; in a nutshell, it makes use of a function that “lazily” replicates itself (which is the same idea as in Haskell). ↩︎“Generics” is the typical term in non-functional languages. ↩︎

This doubtlessly happened many times, but there’s one representative tableau in my memory. ↩︎

Present me is no stranger to this feeling: when I was in college, I used to go to math club talks, some of which were especially dense. There was very little technical gain I received from going (I didn’t understand a tenth of what was explained), but I liked getting a taste of what pure math really looked like, and being reminded (and spurred forward) by my ignorance in virtually everything. There was free pizza too. ↩︎

Given enough time and energy, of course (as I said above, it took me a while to understand

fix). ↩︎Don’t get me wrong: some sections were very difficult to grasp (I eventually started skipping the proofs and metatheory sections to save time). But never too difficult. ↩︎