Using a Chromebook as a CS Student

June 26, 2023

There seems to be a notion that owning an expensive computer is necessary to study computer science. While I do think that buying the most expensive notebook at Best-Buy would probably be the most convenient option (in the short-run, at least), after carrying around a $90 Chromebook every day of my freshman year, I found that computational power and software compatibility alone isn’t what makes a good computer.

How it Began

I used Chromebooks on a daily basis throughout my middle-school and high-school years. Throughout that time, I became pretty familiar with their limitations (and some workarounds), but ultimately I used a Windows laptop for all my programming tasks, because I didn’t know of a way to run code on a Chromebook outside of the browser.

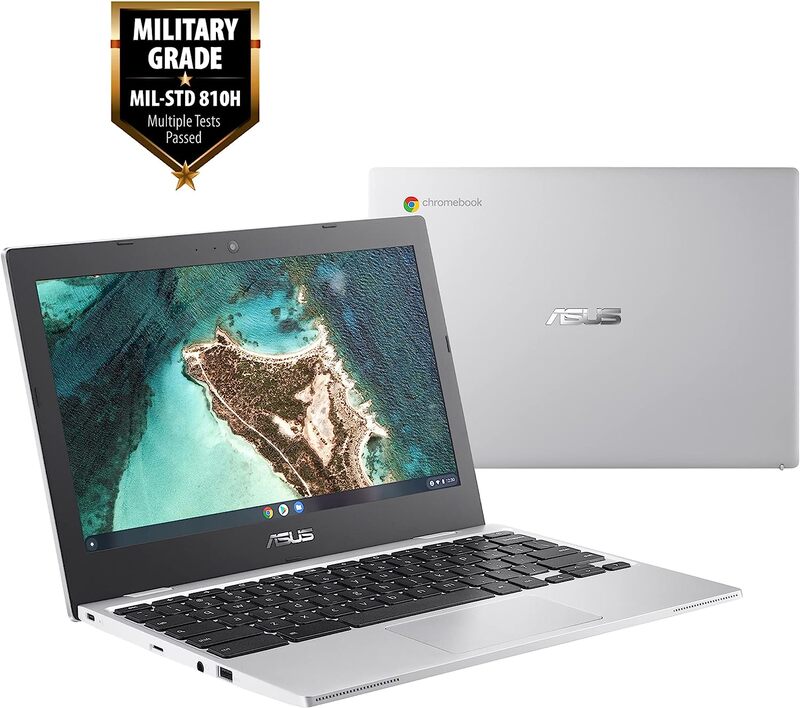

Though I am no shopping enthusiast, on the evening of Black Friday 2021, I found myself on Amazon, where I came across “flash-deal” on an Asus CX1 Chromebook, for $90, which I jumped on. At the time, I had no intention of ever using it as a daily-driver, but I thought the deal was pretty good, and if nothing else, I could use it for a project, or it could serve as an emergency backup for my Windows laptop.

I used it sparingly for several months after that; during this time I found an “enable Linux” button in the settings, and I played around with the terminal, which I (sort of) knew how to use through a conglomeration of sources, namely Windows Batch Scripting (which was actually how I first discovered “programming”), the Windows Command Prompt in general, and Hacknet.

I had been struggling for a while to write curses-style programs in c using the dreaded windows.h (poker was the only one I managed to finish), and I eventually came across ncurses, which was a godsend in comparison, but only worked on Unix-based systems. For the first time ever, I found something that I couldn’t do on Windows that I could do on a Chromebook (yes, there are work-arounds to get a Unix-style terminal on Windows, but I was not aware of any that worked as effortlessly as Chrome’s did, and the main point of having the program in the terminal was for native support). I never actually finished an ncurses project on the Chromebook, but the process made me a little more familiar with Bash and Linux in general.

Around this time I had also had made a ground-breaking discovery of vim, and I had switched to gVim full-time on my windows computer, so when I worked on learning ncurses, I was able to feel comfortable editing text in the terminal; I doubt I would have stuck with it if I had to use nano instead.

I spent most of my time over the summer of 2022 learning Java and x86 Assembly (MASM), the latter of which I (unregrettedly) used Visual Studio for (debugging assembly would have been significantly tougher without a debugger), so I again laid the Chromebook aside, but in the Fall, I began my CS degree at UW, where I carried the Chromebook around every day of my freshman year, despite also owning a windows laptop.

This was viable for me mostly because I was able to adjust my programming workflow from IDEs and the windows environment into the terminal. Any university-related (and most class-related) tasks were completed with the browser, which (of course) has good native support on ChromeOS, which just left the programming-related tasks to the Linux virtual machine. I had already made the switch to vim, and rudimentary knowledge of Bash allowed for program compilation and file management. I was also able to (with little effort) install some GUI programs like musescore and anki, for which I previously had to dust off my windows laptop to use. After a few months of using the Chromebook, I was able to retire my windows laptop to the bottom of my cabinet, under my old homework, only to be taken out in emergencies, when I needed an old file. Not only was I able to do (essentially) everything I wanted on Chrome + Linux, I preferred the workflow of using the terminal.

The Downfall

It turns out that most of the reasons I liked Chrome were directly due to the Linux virtual machine. Chrome provided a few conveniences (an optimized browser, excellent battery-life, built-in screenshot and screen recording, native Chrome apps), but there were also several of annoyances of using a VM alongside ChromeOS, like the lack of access to hardware (webcam, usb ports => can’t encrypt drives directly) and limited support for keybindings.

The biggest deal-breaker for me, however, was the window manager. Though Chrome’s keybinds for window navagation are comparable to other operating systems, I wanted more ergonomic (i.e. keyboard-only) control of windows and tabs, especially with such a small screen. While this was no problem in vim (with windows and tabs), it was really inconvenient trying to pull multiple windows side-by-side in default window manager (which Chrome does not let you change). My solution to this was to run dwm in a nested x-server (with xephyr), which worked surprisingly well, except for one fatal flaw: ChromeOS’s native browser couldn’t be run by the VM (and therefore couldn’t become a window in dwm), but any alternative browser that was ran through the VM was ungodly slow. The solution to this was to use two “workspaces”, one with a xephyr window running the x-server running dwm, the other an empty ChromeOS workspace where a Chrome browser could be run. A four-fingered-swipe on the touchpad could be used to switch between workspaces, and though the problem of not having a browser alongside a terminal remained, a regular ChromeOS terminal could be opened in the Chrome workspace, which was somewhat annoying, but mostly good enough. The worst part about this setup was trying to copy/paste between the workspaces. Since (for security reasons) the VM has no access to Chrome’s keyboard, and I doubted that Chrome had a convenient way to modify the VM’s clipboard, I was out of luck. The workaround was to open the desired file (to paste into) in the ChromeOS terminal and paste it in that way, but for some reason (probably because of the mouse-control support), vim didn’t allow the usual right-click-to-paste in Chrome’s terminal, so the file would have to be opened in Chrome’s native text app, or even worse, nano.

While most of these issues were relatively minor, it still bugged me that there was no way I could fix them. For a while I considered wiping my Chromebook and trying to install Linux directly on it, but I had a sneaking suspicion that the browser and battery life wouldn’t be nearly as desirable as they were on Chrome. Luckily for me, I had a dusty laptop in my cabinet that was effectively as good as new, because I used it so sparingly. I figured I ought to put it to use somehow, so I installed Arch Linux on it, which allowed me to do everything that I had wanted to do on my Chromebook but had previously been unable to do, and has since become my daily-driver. Battery life and replacement expense still remain issues, however.

Should you?

Pros

- 6 to 12 hours of battery life (seriously) (no need to carry around a charger)

- Durable (apparently military grade)

- Dispensable (cheap replacement => easy to try, risk of carrying around is low)

- Unattractive (I doubt anybody would want to steal it)

- Linux (opportunity to learn (Command-line, GNU Coreutils, Scripting, etc.))

Cons

- Slow (at times of intensive computation)

- Virtual machine limitations

- Linux (must tinker to do some things)

- Other cons of ChromeOS (some of which are shared with all other proprietary operating systems)

Details aside, I think that Chromebooks are a viable option for CS majors, though they’re not usually given credit as such. I probably wouldn’t recommend the sole use of a Chromebook to students not familiar with Linux, but I do think that the advantages of Windows and Mac (for the purposes of CS students) over Chrome + Linux-VM are nominal. Additionally, using a Chromebook encourages using the terminal (tough in the short-term, beneficial in the long-term) and discourages video games (attractive in the short-term, useless in the long-term), and offers a way to ease into Linux, while maintaining a (probably) familiar environment, ChromeOS. Plus it’s another way to save a few bucks, which is far from unnecessary for us college students.