Why Haskell is a Great Language

April 1, 2024

No, this is not an April Fools’ Day joke.

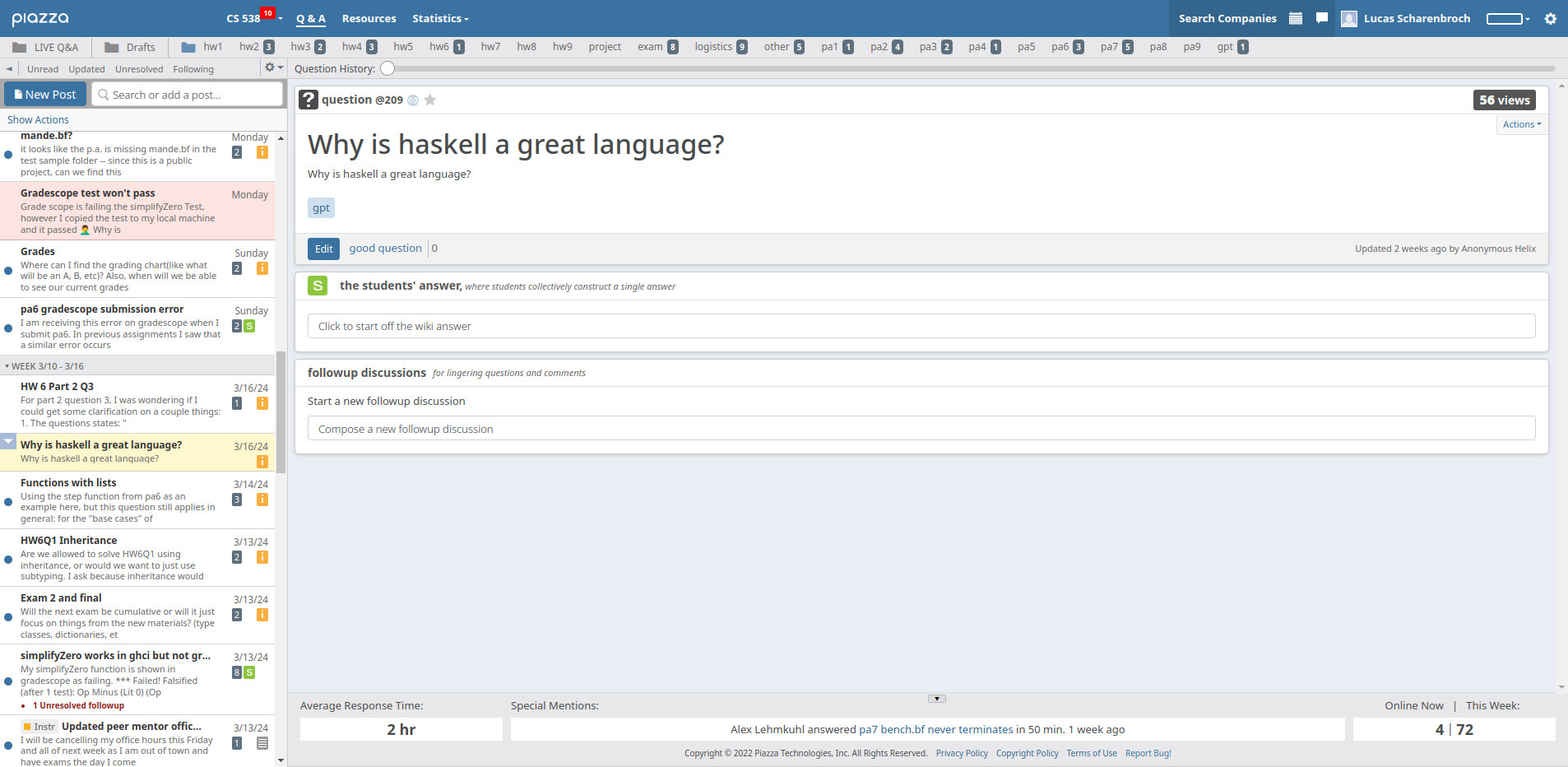

I’m currently taking a class on programming languages as a part of my CS degree at UW. The class briefly touches on Haskell, and somebody posted the following question to Piazza1.

The question is almost certainly a joke: our professor set up a bot that will generate responses to posts tagged with “gpt”: this question is likely a ploy to see what sort of response the LLM will give. I find it to be a very compelling question, though, and I was inclined to write a response to it, but I wasn’t able to come up with a concise and compelling response in after a few minutes. I’ve decided to write a response to the question in a blog post in order to give a more complete response and to more clearly understand the reasons I2 love writing Haskell.

Safety

Haskell is memory safe, statically typed, and purely functional, which3, together, provide a lot4 of guarantees about programs that successfully compile.

In other languages, running after compilation (or just running) is so consistently disappointing that I’ve become conditioned to expect failure. When I started using Haskell, I was shocked by the frequency that my programs ran as expected upon compilation. It’s a glorious feeling.

Memory Safety

There’s no manual memory allocation or access in Haskell, so that class of problems is eliminated.

Static Typing

Haskell is statically typed, therefore programs that compile have correct type signatures and matched function arity and parameter types.

Types are not nullable5, and polymorphism is done via generics and ADTs rather than subtyping, so there are no null-pointer or subtype-casting errors.

Purity

Every variable is immutable, and there are no references/pointers, and no bugs related to ownership or unexpected mutation.

All functions are pure, which means that functions can’t have side effects: the return value of a function is solely determined by its inputs, and applying (calling) a function has no impact on the outside world. This forces code to be modular and simple by default, and it discourages6 the bug-prone idiom of void-returning-functions and global state.

Expressivity

Haskell has the ability to clearly7 and concisely express most common8 transformations of data. Haskell code is usually shorter and easier to read than code in other languages.

As an example9, here’s a solution to the classic Trapping Rain Water problem…

In C++:

int trap(vector<int>& height) {

int N = height.size();

vector<int> left(N), right(N); // largest on left/right respectively

for(int i = 1; i < N; i++) left[i] = max(left[i - 1], height[i - 1]);

for(int i = N - 2; i >= 0; i--) right[i] = max(right[i + 1], height[i + 1]);

int result = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < N; i++) result += max(0, min(left[i], right[i]) - height[i]);

return result;

}In Haskell:

trap :: [Int] -> Int

trap [] = 0

trap height = sum $ zipWith (-) (zipWith min left right) height

where left = scanl max (head height) (tail height)

right = scanr max (last height) (init height)It’s much easier to be sure of what the Haskell version is doing, and it’s hard to be certain that the C++ version doesn’t have off-by-one-errors. The Haskell version captures the essence of the algorithm, and it’s much more like a description of the solution itself rather than instructions for how a computer should find the solution.

Syntax

Haskell’s many restrictions on types, mutability, and purity greatly narrow the necessary capabilities of the language, and the core syntax is simple as a result. At the most primitive level, Haskell is just a typed lambda calculus with a hand-full of features:

- Define Types (ADTs)

- Express values of those types

- Deconstruct values of those types (do a case-analysis on an ADT and retrieve any inner values it has)

- Define Typeclasses

- Declare Typeclass Instances

- Define Functions

- Apply Functions

The syntax for all of these actions is elegant and minimal. Haskell also provides syntax sugar for many common idioms:

- Guards

- Local Variable Binding (“let” and “while”)

- Do Notation

- Sections

- List Comprehensions

- As-Patterns

- Record Notation

- Infix Operators

Each of these cuts down on boilerplate in a clean and natural way, leaving the resulting Haskell code concise and readable.

Rich Type System

Haskell’s type system has power beyond the wildest dreams of the average working programmer, and it makes type systems of other languages seem comparatively rigid and clumsy.

ADTs, typeclasses, and generic and parametrically polymorphic types very naturally slot in with each other, and form a flexible and expressive toolkit.

Here are a few type signatures in Haskell and their equivalents in Rust and Java.

Haskell:

sort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

fst :: (a, b) -> a

compose :: (b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> cRust:

fn sort<T: Ord>(vec: &mut Vec<T>)

fn fst<T, U>(tup: (T, U)) -> T

fn compose<A, B, C, F, G>(f: F, g: G) -> impl Fn(A) -> C

where

F: Fn(A) -> B,

G: Fn(B) -> C,Java:

static <T extends Comparable<? super T>> void sort(List<T> list)

static <A, B> A fst(Pair<A, B> pair)

static <A, B, C> Function<A, C> compose(Function<B, C> f, Function<A, B> g)Haskell also offers language extensions, which provide many advanced features, such as GADTs, DataKinds, and TypeOperators that provide more fine-grained control over the lambda-calculus of types.

Functional Patterns

What really sets Haskell apart from many other functional and multi-paradigm languages10 is its native support for ideas from category theory, and its adoption of them into its core libraries.

Though concepts like Monads, Monoids and Functors have a steep initial learning curve, once they are understood, they offer a way to bootstrap expressivity and generality, and a much more robust framework for defining the behavior of types (and data transformations, which is the essence of programming).

These mathematical ideas are inherent in the way we write programs; you ignore their existence, but you can’t avoid using them. Haskellers embrace these ideas and use them to their advantage to have a greater understanding of the patterns beneath their code and to write programs that better align with those patterns, which yields a massive gain in expressivity that leads to greater concision, safety, and generality.

The Typeclassopedia is a great resource for understanding these patterns, and the Parsec and Lenses libraries are great examples of the many Haskell libraries that heavily use these patterns.

Flexibility

Though it might seem very stubborn, in some ways, Haskell is quite flexible.

Partial Functions

Though functions must be pure, they can be partial, meaning that they can fail (and crash/panic the program) on some inputs. Using partial functions in production code is discouraged, but it’s very convenient for incremental development.

For example, consider some complexFunction that handles many cases of the input. By using undefined (which panics the program), the function can be compiled and tested without implementing all of the cases.

complexFunction :: ComplexType -> Int

complexFunction complexVariantOne = someComputation

complexFunction _ = undefinedExtensibility

GHC has a plethora of language extensions and compiler options/pragmas that can be used to easily opt-in to various experimental and non-default features. This keeps the core language syntax from becoming overly complex, without sacrificing the ability to alter it when doing so is convenient.

Don’t Take My Word For It

It’s hard to truly appreciate what Haskell (or any language) without writing code in it. I’d urge anybody who is even remotely interested to learn Haskell and decide for themselves what makes Haskell great.

Piazza is effectively a private stack-overflow: it’s a forum for class-related questions that can be asked by students and answered by students and course staff. ↩︎

I’ve only been programming in Haskell in a few months, but I’ve written a fair amount of Haskell in that time. ↩︎

Assuming they aren’t abused. ↩︎

Significantly more than mainstream compiled languages (i.e. C++, Java, Rust, etc.) ↩︎

It’s possible to get the same effect as “null” by using ADTs (Maybe), but the null case must be explicitly handled to retrieve the value. ↩︎

It’s still possible to create the illusion of functions with side-effects by using monads. In the case of the IO monad, functions can actually have side effects in order to allow Haskell to interact with the outside world. ↩︎

In the eyes of fluent Haskellers. ↩︎

Like every language, Haskell expresses some programs more naturally than others. It’s not unreasonable to assume that some pathological algorithms are difficult to idiomatically implement (dp is a good example of this: gradual matrix population is much more naturally written in imperative languages; this blog post from an experienced Haskeller proves that it isn’t just me who thinks this). ↩︎

It’s hard to choose a short example that clearly shows the nuances of how Haskell simplifies some algorithms better than others. This post isn’t intended to have an in-depth comparison of Haskell’s syntax to other languages; I wrote a post about a JavaScript -> PureScript refactoring that’s closer to that realm. ↩︎

e.g. Lisp, Rust, JavaScript ↩︎