Graphing Calculator

March 25, 2023

(Github Link)

I’ve used a variety of calculators over the years (namely for math homework), but none of them have everything I want. The TI-83/84 provides most of the desired functionality, but since it is a physical calculator, it comes with all sorts baggage: weight in backpack, battery (=> need to charge or buy batteries), expensive replacement cost, non-ergonomic button layout (any keyboard that isn’t a keyboard is not ergonomic in my opinion), non-ergonomic user interface (manually setting the window, navigating menus), etc. As a result, even though I own a TI-84, I didn’t think it was worth it to carry it around campus. Instead, I would use Desmos for graphing when I needed that, and I would type equations into the Google search bar for basic calculations. Desmos was convenient and good for graphing, but it didn’t have integration with the numerical calculations, and though Google’s calculator was surprisingly decent, it was not ideal for obvious reasons.

Even though I was dissatisfied with the options, I wanted surprisingly little:

- Command-line-like interface for numerical calculation (easy copy/paste/scroll from history)

- Convenient operators for programming (lg for log2, % for “modulus”, scientific notation)

- Support for binary and hex literals

- Basic graphing and tracing

- Seamless integration between command line and graphing (i.e. “What does this function look like? I’ll just graph it”)

I realized that there is no reason I couldn’t have it all in the browser. I also wanted it to be fast (and I prefer to avoid dealing with Javascript directly), so C++ compiled to WASM was the chosen toolkit.

Recursive Descent Parsing

Parsing mathematical expressions is actually a pretty tough problem because of the way operators work. Order of operations along with the mix of prefix and infix operators and the properties of nested parenthesis call for a nuanced algorithm: Recursive Descent Parsing. Though there are ways around it, like the Shunting yard Algorithm, I wanted stronger control of expressions (for things like variable assignment) and I wanted to get a working parser to make sure I understood it. In the process of getting it working, I found myself coming back to this video by hhp3.

Before parsing, the text input is “tokenized” (i.e. strings of digits is turned into a sequence of objects, representing numbers, variables, and operators). This is usually done with regular expressions. Each token is referred to as a “terminal symbol” during parsing (loosely because recursion bottoms out (terminates) upon reaching terminal symbols).

/*

* Terminal symbols: three (3) types.

*

* (1) (VAR)iable identifier:

* - A (letter (case sensitive) or underscore) followed by zero or more (letters, underscores, or

* digits).

* - Regex: "[a-zA-Z_][a-zA-Z_0-9]*".

*

* (2) (NUM)eric literal

* - A "basic" decimal floating point literal in base-10.

* - (one or more decimal digits)

* - [(one or more decimal digits)].(one or more decimal digits)

* - Regex: "(([0-9]*\\.[0-9]+)|([0-9]+))".

* - A "scientific-notation" decimal floating point literal in base-10.

* - ("basic" floating point literal)(e or E)[-](one or more decimal digits)

* - Regex: "(([0-9]*\\.[0-9]+)|([0-9]+))((e|E)-?[0-9]+)".

* - Leading '-' symbols are ignored, as they are handled as a unary operator during gramatical

* parsing.

* - A binary literal

* - (a sequence of 1s and 0s with a leading "0b" or "0B")

* - Regex: "(0[bB][01]+)".

* - A hexidecimal literal

* - (a sequence of hex characters (not case-sensitive) with a leading "0x" or "0X")

* - Regex: "(0[xX][0-9a-fA-F]+)"

* - Regex: "((([0-9]*\\.[0-9]+)|([0-9]+))((e|E)-?[0-9]+)?)|(0[bB][01]+)|(0[xX][0-9a-fA-F]+)".

*

* (3) (OP)erator symbol

* - "+", "-", "/", "*", "//", "%", "^", "(", ")", "=", "==", "!=", ">", "<", ">=", "<=" ",", "'"

* - Regex: "\\+|-|\\*|//|/|%|\\^|\\(|\\)|=|==|!=|>|<|>=|<=|,|'"

*/Then the string of tokens is “parsed”. The basic idea is that every statement is made up of recursively defined parts. We use “nonterminals” (represented here with uppercase strings: S, E, T, F, X, FN, etc.) to make intermediate groups of symbols during the recursive process. S denotes the statement, E denotes an expression, T denotes a term, F denotes a factor, and X denotes an exponential (note that these names don’t necessarily imply that the respective operation is actually being performed (i.e. exponentials need not involve exponentiation), but rather that the tokens grouped into those nonterminals are being parsed at that level of precedence (e.g. an expression in parenthesis must be parsed before it is used as an exponent, so any parenthetical must be parsed into an exponential before it becomes a factor)). These nonterminals are recursively made up of other terminals and nonterminals through a set of “rules” (recursive matches) that are defined by the grammar. The algorithm itself consists of a set of parseY functions (Y here is a placeholder for the name of a nonterminal), one for each nonterminal; the functions take a pointer to the current position in the token array, and attempt to find a match for each rule for Y by calling the respective parseY functions. For example, a statement must consist of exactly one expression, so it only has one rule: “S -> E$” (where $ denotes end of the token array). Thus parseS simply calls parseE (which we inductively assume will correctly parse an expression), and checks that the end of the token array has been reached; if not, it returns null as signal that parsing a statement failed. An Expression (E) can be made up of any assignment or comparison or a sum (or difference) of terms (note that such sum of more than two terms cannot be recursively handled, because 1 - 1 - 1 != (1 - 1) - 1). A term (T) is made up of factors (F) multiplied/divided together (or if there is no multiplication or division, a term is simply any factor (the {} denote “match what is inside 0 or more times; as many times as possible”)). A factor (F) is made up of exponentials (X) exponentiated with each other. Exponentials are made up of numeric literals, variable literals (identifiers), function literals, parenthesized expressions, or negated exponentials. Observe that the hierarchy of the grammar defines how operators are parsed: it is laid out in such a way that any valid statement nonterminal must be a valid statement by the order of operations, and the tree formed by the parsing algorithm (each nonterminal can keep a pointer to the symbols that it is made up of) represents the order of evaluation for that expression.

/*

* Grammar Rules:

*

* S -> E$

*

* E -> VAR = E

* -> FN = E

* -> T {(+|-) T} == E

* -> T {(+|-) T} != E

* -> T {(+|-) T} < E

* -> T {(+|-) T} <= E

* -> T {(+|-) T} > E

* -> T {(+|-) T} >= E

* -> T {(+|-) T}

*

* T -> F {(*|/|//|%) F}

*

* F -> X {^ X}

*

* X -> -X

* -> (E)

* -> NUM

* -> VAR

* -> FN

*

* FN -> VAR{'}(ARGS)

* VAR(ARGS)

*

* ARGS -> {E {, E {, ...}}}

*/

/*

* S -> E$

*/

unique_ptr<TreeNode> parseS(vector<unique_ptr<Token>>& tokens, int i) {

int j = i; /* j is used as a dispensable copy of i that can be passed

* (by reference) to other parseY functions */

if(j == tokens.size()) return nullptr; // reached end of tokens

unique_ptr<TreeNode> tree = parseE(tokens, j);

if(j != tokens.size()) return nullptr; // expression doesn't span all tokens

i = j;

return tree;

}

/*

* E -> VAR = E

* -> FN = E

* -> T {(+|-) T} == E

* -> T {(+|-) T} != E

* -> T {(+|-) T} < E

* -> T {(+|-) T} <= E

* -> T {(+|-) T} > E

* -> T {(+|-) T} >= E

* -> T {(+|-) T}

*/

unique_ptr<TreeNode> parseE(vector<unique_ptr<Token>>& tokens, int& i) {

int j = i;

if(j == tokens.size()) return nullptr; // reached end of tokens

// -> VAR = E

if(tokens[j]->is_var() && j + 1 != tokens.size() &&

tokens[j + 1]->is_op() && tokens[j + 1]->str_val() == "=") {

/* ... parse the E on the RHS and return the tree node ... */

}

// -> FN = E

unique_ptr<TreeNode> fn = parseFN(tokens, j);

if(fn != nullptr && j != tokens.size() && tokens[j]->is_op() &&

tokens[j]->str_val() == "=") {

/* ... parse the E on the RHS and return the tree node ... */

}

// -> T {(+|-) T} == E

// -> T {(+|-) T} != E

// -> T {(+|-) T} < E

// -> T {(+|-) T} <= E

// -> T {(+|-) T} > E

// -> T {(+|-) T} >= E

// -> T {(+|-) T}

une_ptr<TreeNode> lhs = parseT(tokens, j);

if(lhs == nullptr) return nullptr; // failed to read term

// T$ or T? (where ? isn't one of the above options) => skip loop

// ==, !=, <, <=, >, >=, +, or - => loop

while(j != tokens.size() && tokens[j]->is_op()) {

string op = tokens[j]->str_val();

if(op == "==" || op == "!=" || op == "<" || op == "<=" ||

op == ">" || op == ">=" || op == "+" || op == "-") j++;

else break;

unique_ptr<TreeNode> rhs = (op == "+" || op == "-") ? parseT(tokens, j) : parseE(tokens, j);

if(rhs == nullptr) {

i = j - 1; // token before op

return lhs;

}

// continue loop for + and - to maintain order of operations

if(op == "+") lhs = make_unique<AdditionNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == "-") lhs = make_unique<SubtractionNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else {

i = j;

if(op == "==") return make_unique<EqualityNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == "!=") return make_unique<InequalityNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == "<") return make_unique<LessThanNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == ">") return make_unique<GreaterThanNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == "<=") return make_unique<LessOrEqualNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

else if(op == ">=") return make_unique<GreaterOrEqualNode>(std::move(lhs), std::move(rhs));

}

}

i = j;

return lhs;

}

/* ... other parseY functions ... */In a normal calculator, the parseY functions could simply return floating point values (and throw an exception or return some sentinal value for a failed parse), so the result of the expression would be the return value of parseS, but in order to have graphing and function assignment capabilities, the expression tree itself must be remembered. I used this as an opportunity to apply some of those OOP skills (unique_ptr<TreeNode> => polymorphism!). I also was able to use similar functionality for the Token (terminal symbol) classes. This provides convenient ways to get strings and double values for any expression: the parent node (in general) doesn’t need to know the type of its children; it can simply call eval() or to_string() to get the corresponding value from the child subtree.

struct TreeNode { // Abstract superclass for all other node types

virtual string to_string() = 0;

virtual double eval() = 0;

virtual bool is_var() { return false; }

virtual ~TreeNode() { }

};

struct Token {

virtual string to_string() = 0;

virtual string str_val() { return ""; }

virtual double dbl_val() { return NAN; }

virtual bool is_var() { return false; }

virtual bool is_num() { return false; }

virtual bool is_op() { return false; }

virtual ~Token() { }

};Functions and Variables

All functions and variables are kept in a hashtable with their names (strings) as keys. These tables are separate, so a variable and function can share an identifier. Functions can be defined from the command-line with the straightforward notation: “f(x, y) = x + y + z”. The parsed tree of the right-hand-side of the equal-sign is kept internally in the function table. When the function is called, the tree is evaluated as normal, except identifier lookups to the parameter names are caught and redirected to return the argument values. Any non-argument parameters are treated as usual variables, so in the case of f, z’s value would be evaluate as if it were typed literally by the user.

Built-in functions are more straightforward, as their argument values can be passed directly into a backend function. I was able to make use of some template metaprogramming with the class “NDoubleFunction” (that, as you might expect, takes n doubles and returns 1 double).

Some non-calculation functions are also defined for user-interaction with the backend (e.g. “graph”, “ans”, and “clear”). These functions have some funny implications when used in the same context as standard math functions (e.g. trying to graph the graph function; trying to take the derivative of the clear function, etc.). I tried to catch all such bugs that I foresaw actually coming up with daily-use, but I admit that I didn’t bother to think of (nor prevent) all of these cases, so feel free to break the calculator and blame it on my poor design.

Math

Even though my degree’s calculus requirements are behind me, I still wanted to program numerical derivative with Lagrange’s Notation instead of the ugly nderiv notation used by the TI-84. It was a simple addition to the parser, and aside from the non-calculation functions described above, it works on any built-in function (though I don’t think I’ve ever used it for that purpose).

Numerical differentiation is surprisingly trivial: the formula is: (f(x + step) - f(x - step)) / (2 * step), where step is some small constant, which is pretty much the definition of the derivative. Floating point rounding errors are an issue, of course, and in this case, I tried a few values of step to find one that worked sufficiently (1e-6). The step size can be changed from the command-line by changing the “DERIV_STEP” variable.

Higher-order derivatives don’t seem to work well with this formula, however (floating point rounding errors magnify), so anything higher than a third-derivative is pretty much guaranteed to be garbage.

I also implemented numeric integrals, which are calculated as Midpoint Riemann Sums.

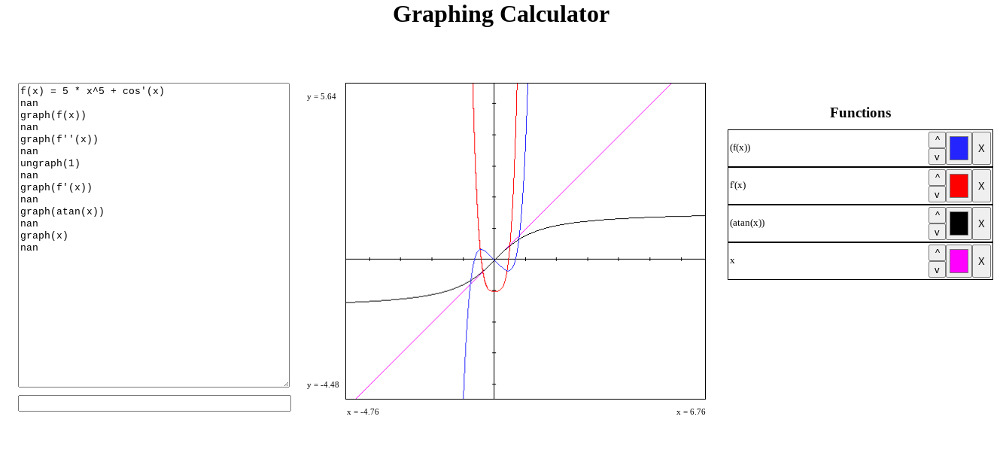

Graphing

Graphing uses a similar parameter replacement procedure as user-defined functions, except that x is the only parameter, and it is always replaced.

The graphing algorithm is intuitive: imagine a vertical line being scanned along the graph window from left to right. The intersection of this vertical line with the graphed function at each horizontal pixel is plotted. The only issue with this is that steep curves become dotted lines if only one pixel is drawn. To prevent this, a vertical segment of pixels, with height equal to the change in y value (from the previous intersection), is drawn along the respective part of the vertical line. The other computations in the draw function are to determine the real x and y values (on the plane) correspond to the pixels.

// draws graphed_functions[index] to graph_buffer

void draw(int index) {

double old_x_value = get_id_value("x"); // x is used as the drawing variable - save its old val

// x_c means "x on canvas" (uses int units), x_p means "x on plane" (uses float units)

double x_ratio = (x_max - x_min) / (graph_width);

double y_ratio = (graph_height) / (y_max - y_min);

vector<int> y_c_vec; // holds the value of y_c at each x_c.

for(int x_c = 0; x_c < graph_width; x_c++) {

double x_p = x_min + (x_c * x_ratio);

set_id_value("x", x_p);

double y_p = graphed_functions[index]->eval();

int y_c;

if(isinf(y_p) || isnan(y_p)) y_c = INT_MAX;

else {

y_c = (y_p - y_min) * y_ratio;

y_c = graph_height - y_c; // 0 = bottom => 0 = top

}

y_c_vec.push_back(y_c);

draw_point_vector(y_c_vec, index); // draws the points in y_c_vec, connecting them (with vertical segments)

}

set_id_value("x", old_x_value);

}