Bash With Floats

August 15, 2023

(Github Link)

The Idea

I recently finished reading the Advanced Bash Scripting Guide (ABS), which, as the name suggests, dives deep into the darkest corners of bash’s functionality. It contains a wide variety of scripts to demonstrate these capabilities; here are a few examples.

- Calculating Pi

- The Fibonacci Sequence (recursion)

- Insertion Sort

- The Sieve of Eratosthenes

- The Knight’s Tour

These scripts are admittedly useless (not to mention inefficient), but that’s not the point: the goal is to demonstrate that such functionality is possible in a script, so that the reader is sufficiently equipped in the rare case where these features come in handy (namely when making a dedicated program would be too inconvenient or inflexible, or when a script is already involved).

Bash has good support for integer arithmetic, and it comes up surprisingly often. There are several ways to work with integers in bash (many of which turn out to be different ways of using the same underlying mechanisms), but the most convenient way is arithmetic expansion keyword: “(())”, and its substitution variant: “$(())”. It supports all of the usual C-style integer operations (+, -, *, /, %, ** (exponentiation), ++, --, &&, ||, !, ==, !=, >, <, >=, <=, ?: (ternary), ~, &, |, ^, «, », =, *=, /=, +=, -=, «=, »=, &=, ^=, |=, comma (separates independent expressions)), and variables can be referenced and modified with the same C-syntax (without requiring quoting or substitutions).

There’s even a C-style for loop construction that uses the arithmetic expansion1.

for ((i = 0; i < 100; i++)) do

echo "i = $i"

doneBash doesn’t have native support for floating-point variables, though: this is presumably because they aren’t nearly as useful as integers, and they’re much less elegant to work with in their string form (all variables in bash are stored as strings (or 1-d “arrays” of strings)). Thus the shell programmer must resort to using external programs (like bc, python, perl, or awk), which results in messy syntax.

For example, say we want to find the average run-time of some arbitrary command, and print a warning if it exceeds a certain threshold. Let’s do it with floats2.

| |

Note the floating-point operations in lines 12, 13, and 17. They require a command-substitution ("$(…)"), a call to an external program (python or bc3), quotes, a print-statement, and variable substitutions. Perhaps this isn’t that bad, but wouldn’t it be convenient4 if we could do something like this instead?

| |

In short, I want a “{{}}”5 operator for floats that is analagous to “(())” for integers. It would also be nice to have a “${{}}” (substitution) version, and a floating-point variable “type”6.

#!/bin/bash

# note that x isn't declared as float yet;

# this doesn't change the script's behavior

{{ x = 5 / 2 }}

echo x = ${{ x += 1 }} # output: "x = 3.500000"

unset x

declare -d x="5 / 2" # "d" stands for "double", as in "double-precision floating point"

# (the f and F options were already taken)

x+=1

echo x = $x # output: "x = 3.500000"The Execution

This project was almost entirely an exercise in understanding bash’s codebase. The vast majority of the lines I wrote were either closely mimicking already-written lines (I especially rode off the back of the arithmetic expansion ((())) operator) or directly copy-and-pasted with minimal modification. This was by no means a trivial task, however.

Bash Code

As one might expect, bash is written entirely in C. It uses (what I would call) an old-fashioned style that involves vertically-aligned opening and closing braces, 8-chars-wide tabs mixed with spaces for indentation, and old-style parameter lists, among other things7. It makes heavy use of macros, preprocessor conditional statements, and memory management. The base-directory of the repository has 125 files (most of the main source-code is in the base-directory).

Below are a few examples that I found interesting or amusing that will hopefully provide an idea for what working with this codebase is like. The line-numbers correspond to my version of the repository at the time of writing this post8.

| |

| |

| |

The collision-handling strategy is chaining: “BUCKET” refers to a slot in the table, and “BUCKET_CONTENTS” is a linked-list-node. I thought that the “HASH_BUCKET” macro (which determines which bucket a string belongs in) was pretty clever: since “(t)->nbuckets” is always a power of 2, “(t)->nbuckets - 1” can be used as a bit-mask to bring any number into the range [0, (t)->nbuckets). No need for modulo.

| |

| |

The longest conditional I’ve ever seen.

| |

| |

An honest function name.

| |

| |

Are there plans to add floats to the official version of bash? It seems unlikely; this union has been around since at least 2009. The struct that is actually used for variables is below: note that “char *” is the only possible type for “value”.

| |

Infrastructure

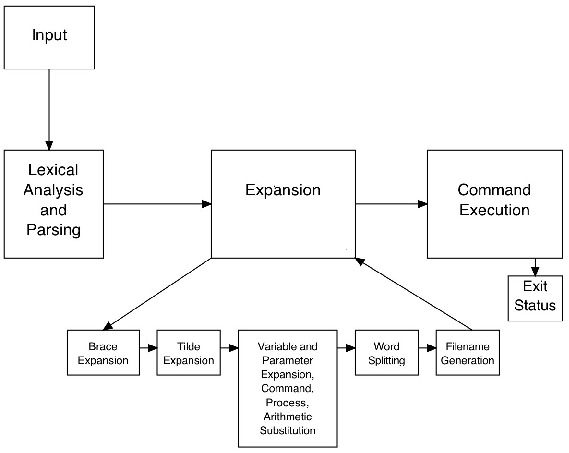

Here’s the big picture of how bash works. It’s from Architecture of Open Source Applications (AOSA), whose bash chapter was written by Chet Ramey, the primary developer of bash. Input is read (from the command line9 or a script), lexed and parsed, expanded (in the many ways described above), then executed.

Each of these steps has a considerable amount of nuance. Parsing is done in yacc/bison10, but the syntactic context of the tokens can change their meaning, so yylex is written manually (instead of using lex/flex). The lexing functions contain the majority of the logic for this step, and there’s even a recursive-descent parser written in parse.y to specifically handle the double-bracket test construct ("[[]]").

Implementation

Adding support for the “{{}}” and “${{}}” operators requires modifying each of the three above steps.

- The text enclosed within “{{…}}” need not be space-separated (i.e. “{{1}}” is valid), so “{{” cannot be a keyword (unlike “[[”); additionally, the text within the “{{}}” construct is treated as if it were double-quoted. Thus the entire construct should be parsed as a single token.

- The “{{}}” command itself needs to run expansion on its contents, and the “${{}}” needs to expand11 to the floating-point-expression’s result.

- The “{{}}” command needs to have a function to execute it.

I also tweaked some of the behavior of assigning variables and the “declare” builtin to add support for the floating-point variable-type.

The evaluation of the floating-point expressions (evaluating the “…” in “{{…}}” ) is a recursive-descent parser that is copied from the arithmetic expansion parser, with the bitwise operators removed and the lexing procedure for a number-token changed.

Is it Useful?

No, not really. Even if I had more than a handful of uses for floats in bash, using this modified version of bash is bad practice and makes my scripts completely non-portable. That being said, the alternative to float-expansions is verbose and slow. It all comes back to the initial question: need this functionality be in a script in the first place? And perhaps a better question: should it be in bash?

This construction turns out to be hard-coded under the hood (there isn’t some underlying property of for-loops that allows this). ↩︎

A cleaner way would be to use an arbitrarily small time unit. ↩︎

Either program could be used for all of the floating-point operations in this example; I used both for the sake of demonstration. ↩︎

It’s worth noting that using external programs like python and bc requires that another process be forked and a lot of initialization to be done (especially in the case of python), which is very sluggish in comparison to using shell builtins. I tested the two scripts above (the example with python and bc and the example with float-expansion), and they ran in 2.188 and 1.125 seconds, respectively; subtracting off the time for the “time $cmd” commands (the average run-time for the sleep command was 0.1049 and 0.1072 respectively), the run-times were 1.139 and 0.053 (!) seconds, respectively. ↩︎

The choice of the double-brace operator is completely arbitrary. I chose it because all of the other double-paren operators are in use ("(())" and “[[]]”), and the float-expansion is very similar to the arithmetic expansion ("(())"), and it shares some properties with the extended test ("[[]]"). ↩︎

As mentioned above, all variables in Bash are strings or arrays of strings, but they also have “types”, which are flags that can be set to tell the shell how to handle assignments and other variable operations. These include “readonly”, “function”, and “integer” (see “help declare” for more details). A variable need not be declared as integer/float to be used in arithmetic/float expansions, but if the variable is declared as int/float, then variable assignments (=, +=) are treated as arithmetic/float expansions. ↩︎

I’ve tried to maintain this style in the code I added, and it has grown on me. ↩︎

The commit hash is e79f07bbd996f2c3385ef0b64c410a9e3e3bc0dc. ↩︎

Readline (The GNU Readline Library) is used for this: is technically a part of bash: it is a library for interaction with and customization of the “command line”. ↩︎

In AOSA, Chet says that he would use recursive-descent instead of yacc/bison if he were to re-write bash. ↩︎

“${{}}” can’t be parsed exactly like “$(())”, because the latter is actually parsed as a command substitution ("$()"); upon seeing the second opening parenthesis, the behavior changes to parse a arithmetic substitution (unless the closing parenthesis isn’t a double-parenthesis, in which case it’s interpreted as a subshell within a command substitution). ↩︎