Computer Algebra System

September 2, 2023

(Github Link)

Note: this project is built directly on top of my graphing calculator application, for which I wrote an independent post (link).

Motive

The idea that computers are capable of symbolic math has always fascinated me. When I first learned algebra, I was made well aware that my calculator was capable of solving only numerical equations. I quickly learned that this wasn’t entirely true: there were some calculators which were able to do algebra, but they were (as I could tell from the model names) exceedingly fancy and expensive, and nobody I knew had them; the only place I heard about then was on the “banned-calculator-list” on rule-sheets of standardized tests.

Though I never did get the chance to use a Ti Nspire CX CAS or HP Prime G2, I did discover online CAS (computer algebra system) tools like Math Papa and Wolfram Alpha, which were immensely helpful for “checking” my math homework.

As I became more familiar with programming and algorithms, these tools became even more impressive because, at first glance, it’s hard to even imagine how such a system would work. Algebra has an inherent abstractness: e.g. what exactly does “solve for x” mean, and how do you know where to even start?

To my delight, this quality doesn’t apply to differentiation, even though it is “more difficult” than algebra1. As opposed to algebraic manipulations (e.g. solving for x or factoring), the algorithm for differentiation is well-defined. In fact, differentiation is literally a set recursively applied rules. Assuming that remembering and correctly applying the derivative rules is not a problem2, differentiation is trivial, and can be easily described to a computer: there is never a doubt as to what to do: there is no moving variables from side to side with uncertainty as done in algebra, and there is no trial and error of choosing u as done in integration. My Calc II professor, Brian Lawrence, said in lecture: “differentiation is a science, integration is an art”.

I thus added “symbolic differentiator” to my queue of potential projects.

Opportunity

I’ve also been interested in doing a project with the TI-84: I’ve been aware of the capabilities of programming the TI-8x since I saw this video when I was in middle school, and I’ve been interested in programming it ever since, but I postponed it for a while because I wasn’t eager to learn TI-Basic for that singular purpose.

I was confident that symbolic differentiation was an easy algorithm, and since I’ve already written two3 recursive-descent parsers for mathematical equations (for my graphing calculator and bash projects respectively), it was too small for a standalone project, so I decided to combine the two ideas and try to write it for the TI-84.

Now I know that a lot of high-schools (and maybe some colleges) allow the use of the TI-8x in Calc exams, so I want to make it clear that my goal was never to enable cheating or any sort of academic dishonesty. Writing such a program for the TI-8x is appealing because it presents a practical challenge in implementation with a novel outcome: put simply, it’s cool to stretch the limits of a calculator’s hardware. Programs that enable symbolic differentiation and more on the TI-8x are already available online, but just for an extra layer of precaution, I planned on withholding the binary (executable) files from publication. I don’t condone cheating, but if students insist on it, I’d rather they learn a thing or two about compiling and assembling programs.

Hacking

The internet has a vibrant community of TI calculator enthusiasts/programmers on sites like Cemetech and ticalc. The sheer volume of programs written for these calculators and the range of abilities of these programs is really impressive. I was also very impressed by the range of open-source tooling available for writing programs for the TI-8x, which includes emulators, assemblers, disassemblers, and compiler toolchains for C/C++. What’s especially cool is that all of this software is written entirely by hobbyists4.

My original plan was to write the symbolic differentiator entirely in eZ80 assembly for the TI84+CE, however, the prototype I wrote in C was over 500 lines, and I wasn’t keen on writing/debugging that much assembly in addition to trying to figure out how to work with the user-interface, also in assembly. I thus decided to write it in C and use the CE-toolchain’s compiler. At this point, I was still deciding exactly how I wanted the program to work (namely the user interface). Every program for the TI-84+CE (that I was aware of) was ran more or less independently of TI-OS (TI’s operating system- the native interface): when launching the program, it took control of the screen, did its thing until termination, then restored control to the usual ui. I could have done this, but ideally, I wanted a program that was integrated with TI-OS: I wanted to add a function called “deriv” that could be called directly from the home menu, instead of trying to re-implement the home menu inside of a program just to add a single function.

I found a program for the TI-83+ called Symbolic that did everything I wanted, so the project essentially morphed into an attempt to port Symbolic to the TI-84+CE.

Long story short, this is easier said than done. The architecture of the TI83+ and TI84+CE is similar but different in a few critical areas. TI-OS allows code that changes its behavior (like making a custom function callable from the home screen) through a feature called “hooks”, which are essentially optional function pointers that are called before/after certain TI-OS routines. TI intended hooks to only be used by official “apps”, and to enforce this, hooks that reside in user memory (where user programs are executed) are not called. “Apps” are stored in flash-memory, and aren’t moved to user-memory when executing, so hooks that are defined in apps work as expected. The key detail here is that TI ensures that normal users can’t make apps by requiring that they are cryptographically signed. The TI-83+ uses a signature with a weak (short) key, which has been brute-forced by calculator enthusiasts, but the same is not true for the TI-84+CE.

A well-known work-around for this is to copy a hook from user memory into a commonly unused location in flash, and hope that it isn’t overwritten / doesn’t overwrite something else. The problem here is that my program is exceedingly long, and makes heavy use of memory allocation, making an issue with memory highly likely. I tried to find a way to call my program from the hook by looking at disassembly to find an appropriate system routine. This worked, but calling the program without moving it to the start of user memory is futile, because all of the non-relative jumps and references are made with the assumption that the origin of the program is at the start of user memory. Thus, in order to use complex functionality from a hook, I needed to move the entire (lengthy) program around in user memory. This had to be done every time any hook I used was called. At this point, I decided that even if I did manage to get the program to run, it would probably take a significant amount of struggling with more similar issues, and I would likely have to make severe limitations to my program to allow it to compile and run gracefully onto TI-84+CE hardware. While this is something I could certainly try, I wasn’t especially excited about it, so I opted to try something else instead.

Redirection

New objective: implement more advanced algebraic algorithms in addition to symbolic differentiation, and add them to my existing graphing calculator project.

It’s only been a few months since I wrote the aforementioned graphing calculator project, but after working with bash’s recursive descent parser, I realized just how poorly written the former was, so I began by completely re-writing it and the explanation of it on my website.

I then read about / implemented the following algorithms and restructured the webpage.

Differentiation

As I said earlier, differentiation is a set of recursively applied rules. Here is the way it was taught to me: (assume that the derivative is being taken with respect to x)

Base-Cases:

- deriv(x) = 1

- deriv(c) = 0

- deriv(cx) = c

- deriv(x^c) = cx^(c - 1)

- deriv(ln(x)) = 1 / x

- deriv(e^x) = e^x

- deriv(sin(x)) = cos(x)

- deriv(cos(x)) = -sin(x)

- deriv(tan(x)) = sec(x)^2

- deriv(asin(x)) = 1 / sqrt(1 - x^2)

- deriv(acos(x)) = -1 / srqt(1 - x^2)

- deriv(atan(x)) = 1 / (1 + x^2)

Chain-Rule:

- For any of the above base-cases, you may replace “x” with “u” on both sides of the equality, and multiply the right-hand-side by deriv(u) (that is, for any above f(x) = g(x) it also holds that f(u) = g(u) * deriv(u)).

Recursive-Rules:

- deriv(u + v) = deriv(u) + deriv(v)

- deriv(u * v) = deriv(u) * v + deriv(v) * u

- deriv(u / v) = (v * deriv(u) - u * deriv(v)) / v^2

I don’t disagree that this is a good way to teach it, but I find it particularly curious that the recursive nature is hidden first (by just showing the base-cases where u = x), then applied later with the chain rule, instead of first describing every rule with the reduction baked in (except deriv(x) and deriv(c)), then explaining why the base-cases hold (because the derivative of x is 1, so the deriv(u) factor can be ignored). The following are the rules used by my algorithm.

Base-Cases:

- deriv(x) = 1

- deriv(c) = 0

Recursive-Rules:

- deriv(u^v) = u^v * deriv(v * ln(u))

- deriv(u / v) = deriv(u * v^-1)

- deriv(u * v) = deriv(u) * v + deriv(v) * u

- deriv(u + v) = deriv(u) + deriv(v)

- deriv(-u) = -deriv(u)

- deriv(ln(u)) = deriv(u) / u

- deriv(sin(u)) = cos(u) * deriv(u)

- deriv(cos(u)) = -sin(u) * deriv(u)

- deriv(tan(u)) = sec(u)^2 * deriv(u)

- deriv(asin(u)) = deriv(u) / sqrt(1 - u^2)

- deriv(acos(u)) = -deriv(u) / srqt(1 - u^2)

- deriv(atan(u)) = deriv(u) / (1 + u^2)

Note the absence of the quotient-rule (quotients are reduced to products), and the chain rule (which is implicitly applied everywhere it was appropriate). The following is the pseudocode for the differentiation algorithm.

diff(tree):

if tree is a number, return 0

if tree is x, return 1

otherwise, if tree is an operation in [^, /, *, +, -, ln, sin, cos, tan, asin, acos, atan], perform the reduction and return

otherwise, throw an error: not differentiable

Simplification

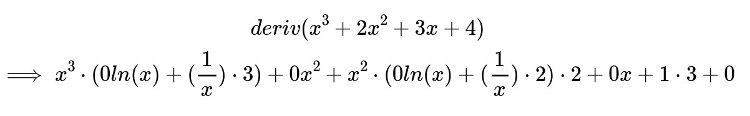

It turns out that, when following the above rules for differentiation, the resulting equation tree can be pretty ugly, for example.

The simplification algorithm results in the following.

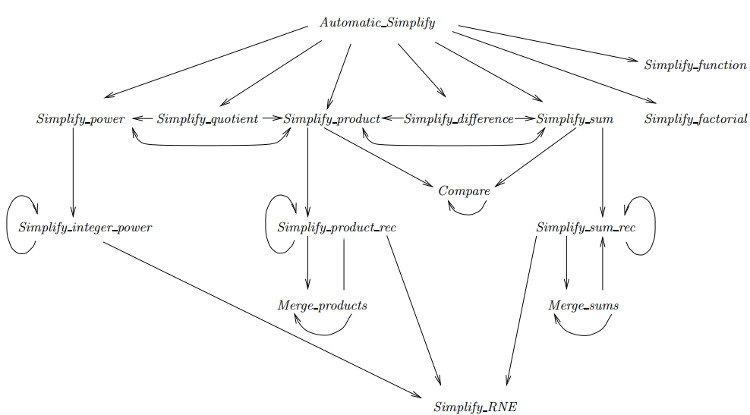

I consulted a textbook (Computer Algebra and Symbolic Computation: Mathematical Methods by Joel S Cohen) for the algorithm for this, and it was surprisingly almost identical to how I would implement it naively: it consists almost entirely of applying trivial rules (like 0 * u = 0, 1 * u = u), combining nested binary sums/products into n-ary sums/products, and comparing/combining their terms/factors. Probably the most useful idea from the book’s algorithm is the development of a well-defined ordering of terms/factors in a sum/product: if this ordering is always followed, terms/products can be merged in a merge-sort like routine to maintain the order, and only adjacent terms need to be compared to check for matches.

The following is a diagram from the book describing the algorithm in its entirety: it makes things seem more complicated than they are, in my opinion, but nevertheless it’s a good illustration of exactly how the parts are interconnected.

Simplify_product_rec and Simplify_sum_rec are probably the most complex of the bunch; Simplify_RNE stands for “simplify rational number expression”; I opted to leave this part out, because I love real numbers.

Expansion

Simplification doesn’t distribute factors over sums or exponents over products, because that sometimes doesn’t make the equation simpler. Thus those things are left to expansion. It works exactly as you’d expect.

Reflection

I’d like to explore algorithms for factoring, general algebraic solving, integration and differential equations, but from what I’ve read, these algorithms are pretty nuanced, so I’m holding off on diving too deeply on any of them right now.

If I do choose to implement any of those, I may rework this project again, or rewrite it in a completely different language / platform.

I’m much happier with the code now than before the initial refactor, but it still strikes me as way too verbose:

ideally, returning a new equation-tree-node (TreeNode) with a couple of nested operations should be relatively concise; right now, that it takes at least 10-15 lines, which

is almost entirely boilerplate (a lot of uniq_ptr

According to my highly unscientific observations that Calculus 1 has a reputation for difficulty and is considered an advanced class. Differentiation does admittedly require a lot of algebra, though, so perhaps the difficulty comes from the algebra involved. ↩︎

Easier said than done… (for a human). ↩︎

The bash one was admittedly copied/tweaked, but I learned a lot from reading it, and I used that knowledge to rework the parser for my graphing calculator. ↩︎

There is some proprietary tooling, but every tool I used was open-source. ↩︎

It’s thankfully much less bug-prone than in C, where it involves manual (not smart-pointer) memory management; I’m glad I didn’t have to figure out what it was like in assembly. ↩︎