Drum-Talk

March 5, 2024

(Github Link)

This project is the intersection of my interests in four areas:

- Compilers

- Functional Programming

- Keystroke Minimization / Extensibility / UNIX Philosophy

- Drumming

It’s a pretty safe bet that nobody except me will actually use this program.

Lore

When drummers1 want to communicate a rhythmic idea without directly playing it2, they often use a specialzed collction of words and sounds, which I will refer to as drum-talk3.

For example, the following might be used by a snare drum player in a marching band.

“paradiddle flamacue three e tripulet gock”

Or the following might be used by a hand-drum player to describe the cáscara rhythm.

“da da duh da duh da duh da da duh”

This should not be confused with beatboxing, whose focus is more on performance and variation in sound emulation rather than rhythmic communication.

Counting

Drum-talk is a superset of a more common counting system used by musicians4.

The system is made up of numbers that denote a beat in the measure:

- “one”

- “two”

- “three”

- …

Words that denote a position in the measure relative to a beat:

- “e” (1/4 of a beat after a beat)

- “and”, “&”, “+” (1/2 of a beat after a beat)

- “ah”, “a” (3/4 of a beat after a beat)

Words that represent rhythms agnostic of location or speed:

- “tripulet” (an intentional mis-pronounciation of “triplet” (3 syllables))

Rudiments

Rudiments are a collection of rhythmic5 idioms that are ubiquitous in marching-band/drum-corps music and frequently used elsewhere. Many of them are not very useful for rhythmic speech6, but the others make up the bread and butter of drum-talk:

- Single Paradiddle - “paradiddle”

- Double Paradiddle - “paraparadiddle”

- Triple Paradiddle - “paraparaparadiddle”

- Paradiddle-diddle - “paradiddlediddle”

- Flam - “flam”

- Flam accent - “flam-accent”

- Flam Tap7 - “flam-tap”

- Flamacue - “flamacue”

- Flam Paradiddle - “flamadiddle”

- Flam Paradiddle-diddle - “flamadiddlediddle”

- Pataflafla - “pataflafla”

- Drag - “drag”

- Lesson 25 - “twenty-five”

- Dragadiddle - “dragadiddle”

- Ratamacue - “ratamacue”

Informal Words

Drummers often ignore formal counting and rudiments and say the rhythm with more natural words.

- “da”, “ta” (long, accented)

- “duh”, “tuh” (short, non-accented)

- “dduh”, “ttuh” (double-stroke)

- “ddut” “ttut” (flam)

Other Words

- “shot” and “gock” refer to rimshots

- “double” refers to a double-stroke, which is two evenly-spaced notes played by the same hand in rapid succession

- “buzz” refers to the technique of the same name (a.k.a. “multiple bounce stroke”)

Formalization

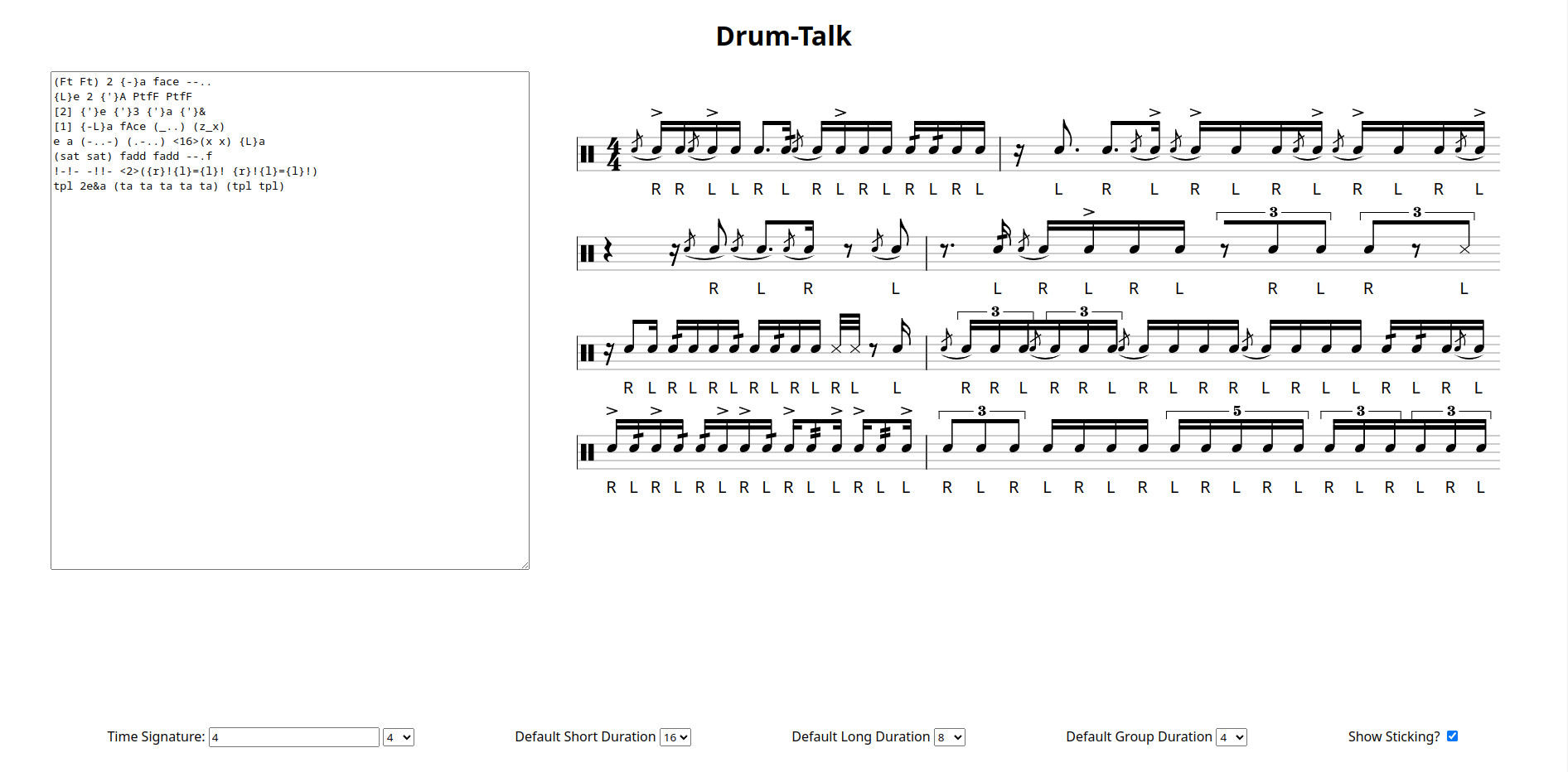

This project attempts to conveniently combine all of the above constructs into a single grammar that can be directly translated into engraved music. Every above word/phrase in double-quotes is valid Drum-Talk3, and there are several additional constructs I’ve added to make it more usable/convenient.

- Abbreviations (“tripulet”<=> “tpl”)

- Capitalization => accents ("{>}x" <=> “X”)

- Modifier Flags for articulations/ornamentals ("{’}tap" <=> “f”)

- Modifier Flags for duration ("<4>roll" is a quarter-note long-roll)

- Note Grouping (tuplets ("(…)" <=> “tpl”))

- Time Specification ("[2] e" => the e of 2; “[2]f” <=> “{’}2”)

- Strong Sticking ("{R}tap" forces a right-stick)

- Weak Sticking ("({r}tap {r}tap {l}tap)" will either be sticked R-R-L or L-L-R, depending on the proceeding stick)

See the language spec at the bottom of the github-pages page for a more complete description of the language.

Compilation

The beef of the computational work of this project is converting text into an internal representation of notes (which can then be drawn to the screen). Compilation is done in PureScript, which is a language very similar to Haskell8 that transpiles to JS (more on PureScript later).

The main pipeline of compilation is best described by the definition of the compile function.

compile :: Settings -> String -> Either String (Array DrawableMeasure)

compile settings = parse settings

>=> timeify settings

>=> (pure <<< alternateSticking)

>=> (pure <<< dissolvePow2Tuplets)

>=> (pure <<< splitEvenTuplets)

>=> toDrawable settings

parse :: Settings -> String -> Either String (Array Word)

timeify :: Settings -> Array Word -> Either String (Array TimedGroup)

alternateSticking :: Array TimedGroup -> Array TimedGroup

dissolvePow2Tuplets :: Array TimedGroup -> Array TimedGroup

splitEvenTuplets :: Array TimedGroup -> Array TimedGroup

toDrawable :: Settings -> Array TimedGroup -> Either String (Array DrawableMeasure)The (<<<) function here is equivalent to Haskell’s (.) (function composition)9.

For anyone unfamiliar with this syntax: the Kleisli-arrow operator >=> is effectively a left-to-right pipeline (like a shell pipe (|)) that allows failure (in this case, failing means returning a String instead of an Array DrawableMeasure). The pure function is just a wrapper for functions that can’t fail, which is necessary for the types to line up.

Parsing

Parsing is relatively straight-forward: the hardest part was trying to decide what data structures to use for the AST, and how they would be (eventually) converted to drawable notes, and what restrictions that those structures posed on parsing.

The main unit of DrumTalk is a “word”, which represents a note or a note-group. It must have at least one of the following:

- An exact time in the measure

- A duration

This gives way to the possible values of a Word:

Absolute Word: Just a timeRelative Word: Just a durationComplete Word: Both a time and duration

data Word = AbsoluteWord Time Note -- implicit duration

| RelativeWord (Tree WeightedNote) Duration -- implicit time

| CompleteWord Time (Tree WeightedNote) DurationThese types have a heavy influence on the parser, because they control how syntax can be grouped.

It’s worth noting that while these types (or the logic behind them) do greatly influence the parser, the types themselves are not nonterminals.

This is because the nonterminals are layed out to minimize their common prefixes (e.g. modified-word is the only nonterminal that begins with a modifier), and these word-types don’t directly align with those nonterminals (e.g. parseModifiedWord has type ParseFn Word because it might return a word of any of the above subtypes).

The following is the BNF and type signatures for the entire parser.

type ParseFn a = ParserT String (Reader Settings) a

-- sentence => (spaces word spaces)+ eof

parseSentence :: ParseFn (Array Word)

-- word => [time-spec] duration-word

parseWord :: ParseFn Word

-- duration-word => [duration-spec] modified-word

-- | [duration-spec] word-group

parseDurationWord :: ParseFn Word

-- modified-word => [modifier] time-artic

-- | [modifier] time

-- | [modifier] misc-sound

-- | [modifier] short-stroke

-- | [modifier] long-stroke

-- | [modifier] rudiment

parseModifiedWord :: ParseFn Word

-- time-artic => spelled-number

-- | "e"

-- | "and"

-- | "a" | "ah"

parseTimeArtic :: ParseFn (Tuple Time Note)

-- time => number | spelled-number

-- | "e"

-- | "and" | "&" | "+"

-- | "a" | "ah"

parseTime :: ParseFn Time

-- time-spec => "[" time "]"

parseTimeSpec :: ParseFn Time

-- spelled-number => "one" | "two" | "three" | "four" | "five" | "six"

-- | "seven" | "eight" | "nine" | "ten" | "eleven" | "twelve"

parseSpelledNumber :: ParseFn (Tuple Natural Boolean) -- (number, isAccented)

-- number => [0-9]+

parseNumber :: ParseFn Natural

-- word-group => "(" (spaces (duration-word | "_") spaces)+ ")"

parseWordGroup :: ParseFn Word

-- rudiment => "flamtap" | "ft"

-- | "flamaccent" | "fac"

-- | "flamacue" | "face"

-- | "pataflafla" | "ptff"

-- | "twentyfive" | "ttf"

-- | "ratamacue" | "rtmc"

-- | "paradiddle" | "padd"

-- | "paraparadiddle" | "papadd"

-- | "paraparaparadiddle" | "papapadd"

-- | "paradiddlediddle" | "padddd"

-- | "flamadiddle" | "fadd"

-- | "dragadiddle" | "dradd"

-- | "triplet" | "tpl"

-- | "swipulet" | "sat"

-- * any syllable of a rudiment may have a modifier

parseRudiment :: ParseFn Word

-- misc-sound => "ta" | "da"

-- | "tuh" | "duh"

-- | "dduh" | "ttuh"

-- | "ddut" | "ttut"

parseMiscSound :: ParseFn (Tuple Duration Note)

-- short-stroke => "tap" | "t" | "." | "!"

-- | "gock" | "shot" | "x"

-- | "buzz" | "z"

-- | "flam" | "f" | "'""

-- | "drag" | "dr" | """

-- | "double" | "d" | "-"

parseShortStroke :: ParseFn Note

-- long-stroke => "roll" | "="

parseLongStroke :: ParseFn Note

-- modifier => "{" mod-flag+ "}"

parseModifier :: ParseFn (Note -> Note)

-- mod-flag => "z" | "-" | "=" | "x" | ">" | "^" | "'"

-- | "f" | """ | "n" | "l" | "r" | "L" | "R"

parseModFlag :: ParseFn (Note -> Note)

-- duration-spec => "<" (2|4|8|16|32) ">"

parseDurationSpec :: ParseFn DurationTiming

timeify converts a list of words to a list of TimedGroups.

timeify :: Settings -> Array Word -> Either String (Array TimedGroup)

data TimedGroup = TimedGroup (Tree WeightedNote) Duration

| TimedNote Note Duration

| TimedRest DurationThe key conversion is the erasure of the notion of Time (offsets relative to the measures/beats).

Words might have Time, Duration, or both, but TimedGroups only have Duration.

Doing this is tricky, because there’s a bit of a circular dependency: AbsoluteWords have implicit duration (their duration must be derived from the times of surrounding notes), and RelativeWords have implicit time (their time must be derived from the times and durations of surrounding notes).

This inherent complexity makes for a pretty convoluted timeify.

Words are first mapped to Times, given the TimeInfo (start-time and end-time-range) of the previous word.

Adjacent TimeInfos are then zipped together to calculate the duration (and rests) corresponding to each Word.

timeify :: Settings -> Array Word -> Either String (Array TimedGroup)

timeify settings words = validateSettings settings *> res

where

zero = MeasureTime (0 % 1)

zeroI = {start: zero, earlyEnd: zero, defEnd: zero}

{timeSig} = settings

wholeWord = RelativeWord (Leaf $ WeightedRest n1) <<< Duration $ sigToR timeSig -- dummy leading whole note

words' = [wholeWord] <> words

res = do

times <- scanlM (wordToTime settings) zeroI words'

let timeDiff = zip times (drop 1 times <> [zeroI])

pure <<< fromMaybe [] <<< tail <<< concat $ zipWith (calcDurationAndRests settings) timeDiff words'

-- assert that the time signature is valid

validateSettings :: Settings -> Either String Unit

-- map Word to TimeInfo given TimeInfo of previous Word

wordToTime :: Settings -> TimeInfo -> Word -> Either String TimeInfo

-- calculate notes/rests (Array TimedGroup) from a word, its TimeInfo, and the TimeInfo of the previous Word

calcDurationAndRests :: Settings -> Tuple TimeInfo TimeInfo -> Word -> Array TimedGroupAnd, of course, the whole thing can fail at any time10, which is why all of these functions’ return types are wrapped in Either String.

Sticking, Tuplets, and Drawing

Conversion from the Array TimedGroup to Array DrawableMeasure involves

- Iterating through each note, in order, updating their stickings accordingly

- Un-grouping

TimedGroups that need not be grouped together (that can be split in half or that are composed entirely of notes of normal values) - Converting

TimedGroups intoDrawableNotes, which assigns regular note-values to grouped-notes (rather than arbitrary natural-number weights) - Grouping those

DrawableNotes into beamed groups, then measures

These are all relatively straight-forward, modulo a few technical details and edge-cases.

Thoughts on PureScript

I’m not a big fan of JavaScript. I respect its power and flexibility and the insane JIT optimizations that make it fast, but none of this helps me get over the fact that it’s an accident waiting to happen. Any attempt I’ve made to write non-trivial code in JS has resulted in a shoddily-glued mess whose runtime-errors I am so well conditioned to expect that I’m dumbfounded by a first-try successful run.

TypeScript is a lot better on the safety front, but it’s still far from being my language of choice.

Since I finished writing my APL Interpreter, my mind’s been tuned to approaching problems from a pure-functional perspective, so I was really excited when I first saw the syntax of PureScript, which is indistinguishable from Haskell in most cases.

My hope was that writing PureScript would be like writing Haskell that could also run in the browser. Though it does a decent job at this, PureScript falls short in a few key areas. It boils down to two main problems:

- PureScript aims to concisely transpile to JS => the layer between PURS and JS is thin, and some JS-isms seep into PURS

- Libraries are greatly fragmented (to avoid unnecessary imports) => many imports

- Native JS types have to be used or converted/to/from to interface with JS (Array/Number/records)

- Records (JS Objects) aren’t very elegant

- Other slight tweaks in syntax (these might have varying reasons)

- No sections

- No undefined

- Typeclass derivations are more clumsy

- Explicit type variables

- No built-in tuple syntax

- The standard functions/libraries are often subtly different from Haskell’s, and it’s easy to reach for a function that isn’t there, or that has an unpredictable name

- PureScript is younger and much less developed than Haskell => the tooling isn’t as good

- Compiler Messages are even more cryptic and imprecise than Haskell’s

- Linting is not as friendly

- Documentation (Pursuit) is harder to navigate, and often less-logically organized

Any one of these problems would be minor in isolation, but they add up to make the language significantly less convenient to work with than Haskell. For me, the benefits are worth these drawbacks, especially as complexity balloons, but PureScript definitely leaves some things to be desired. Luckily, development time can fix many of these issues.

JavaScript < TypeScript < PureScript < Haskell

Engraving

I used a tool called VexFlow for the in-browser engraving. It does pretty much everything I wanted to do within a few API calls.

I decided that writing a “front-end” in TS/Svelte to directly use VexFlow and call the PureScript code would be easier than trying to interface with VexFlow directly from PureScript. This worked very well: I can definitely see the appeal of web frameworks: they make managing dynamic state trivial.

Calling PureScript from TS was also relatively easy: the aforementioned inconveniences of writing JS-like code in PureScript pay off on the other side of the bridge.

Dealing with Algebraic Data Types is pretty hack-y (I used instanceof to check which variant of the type the value was, then .value0, .value1, … to access the member values).

There’s probably a better way to do it.

VexFlow doesn’t have any mechanism for auto measure-formatting, so I had to write code to automatically calculate the positions of each measure. I think there’s a DP Algorithm to minimize the wasted space on the margins, but I stuck to the greedy/naive version for the initial implementation.

The one feature VexFlow doesn’t have (as far as I know) is a “z”-tremolo (buzz roll). I guess it isn’t widely used outside of percussion music. I might try to add it to VexFlow, but for now, “z”/“buzz” functions as a regular tap.

The word “drummers” here is used as a general term for percussionists or musicians alike, or really anybody who vocalizes drum sounds. ↩︎

Speaking out rhythms (rather than playing) can also be used to more clearly communicate how a passage is played, not just what it sounds like. For example, a specific sticking (assignment of hands to notes) is implied by the word “paradiddle”. ↩︎

The phrase “drum-talk” is unfortunately overloaded: I use it to refer to both the language drummers speak, and the language that I wrote a compiler for. The latter will be written with capital letters. ↩︎ ↩︎

The term “musician” implies “‘classically’-trained-musician” throughout this post. I’d suspect that music traditions from other cultures have similar mechanisms for rhythmic communication, though. ↩︎

Rudiments can also include sticking, accents and ornaments (not just rhythm). ↩︎

There is a lot of redundancy in the rudiments, and many of them are variations of each other. 13 of the 40 “essential” rudiment are different variations of rolls, and all of the rest involve either a paradiddle, flam, or drag. ↩︎

“Flam-tap” and “flam tap” are not the same! The former is the rudiment “flamtap”, whose sticking is different from the two words “flam tap”. The latter is an inverted flam tap (alternating sticking). ↩︎

Funnily enough, Hugo (the static-site generator for this site) has no syntax highlighting option for PureScript, so the PureScript code-snippets in this post use Haskell highlighting. ↩︎

This is a PureScript-ism, presumably the result of the use of “.” for accessing members of records (the equivalent of JS objects in PureScript). ↩︎

In its current state, the failure-cases could probably be factored out into a separate check function, but it’s easy to imagine a case where an error wouldn’t be detected without the computation provided in these functions. It’s also inconvenient to have to dig into the data structures twice. ↩︎