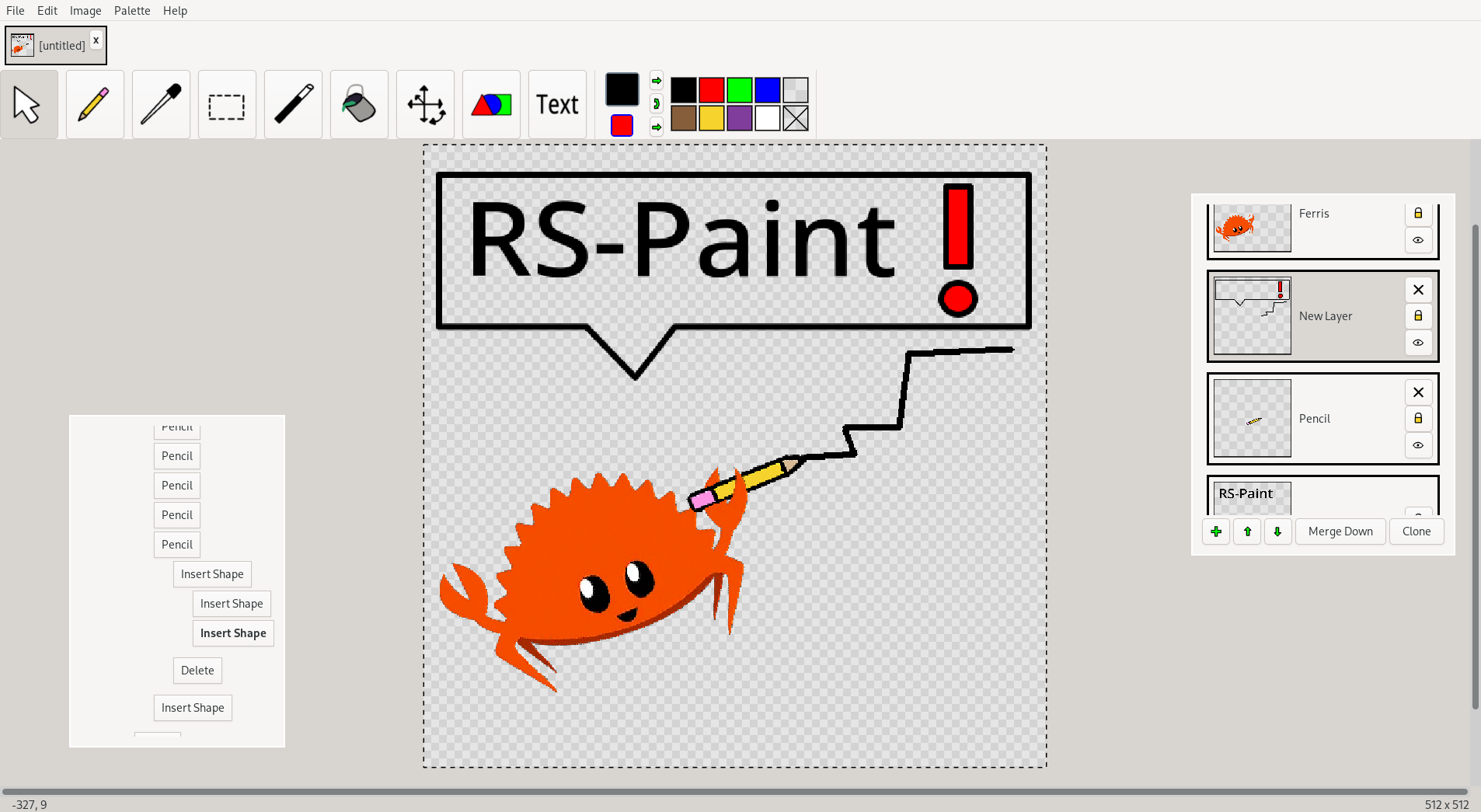

RS-Paint

August 4, 2024

(Github Link)

Motivation

I wrote this program to be “my ideal image editor”. I don’t edit images often, and when I do, I often only reach for a handful of simple operations. I want those operations to be intuitive and highly ergonomic1 (1). That being said, I still need an editor that’s relatively powerful (2) so I won’t be held back by a lack of features. Finally, I expect my editor to be free and natively compatible with Linux (3).

I’ve a tried few mainstream editors, and each of them fails on at least one of these criteria.

- Gimp is quite powerful, but it’s a far cry from ergonomic2 (1).

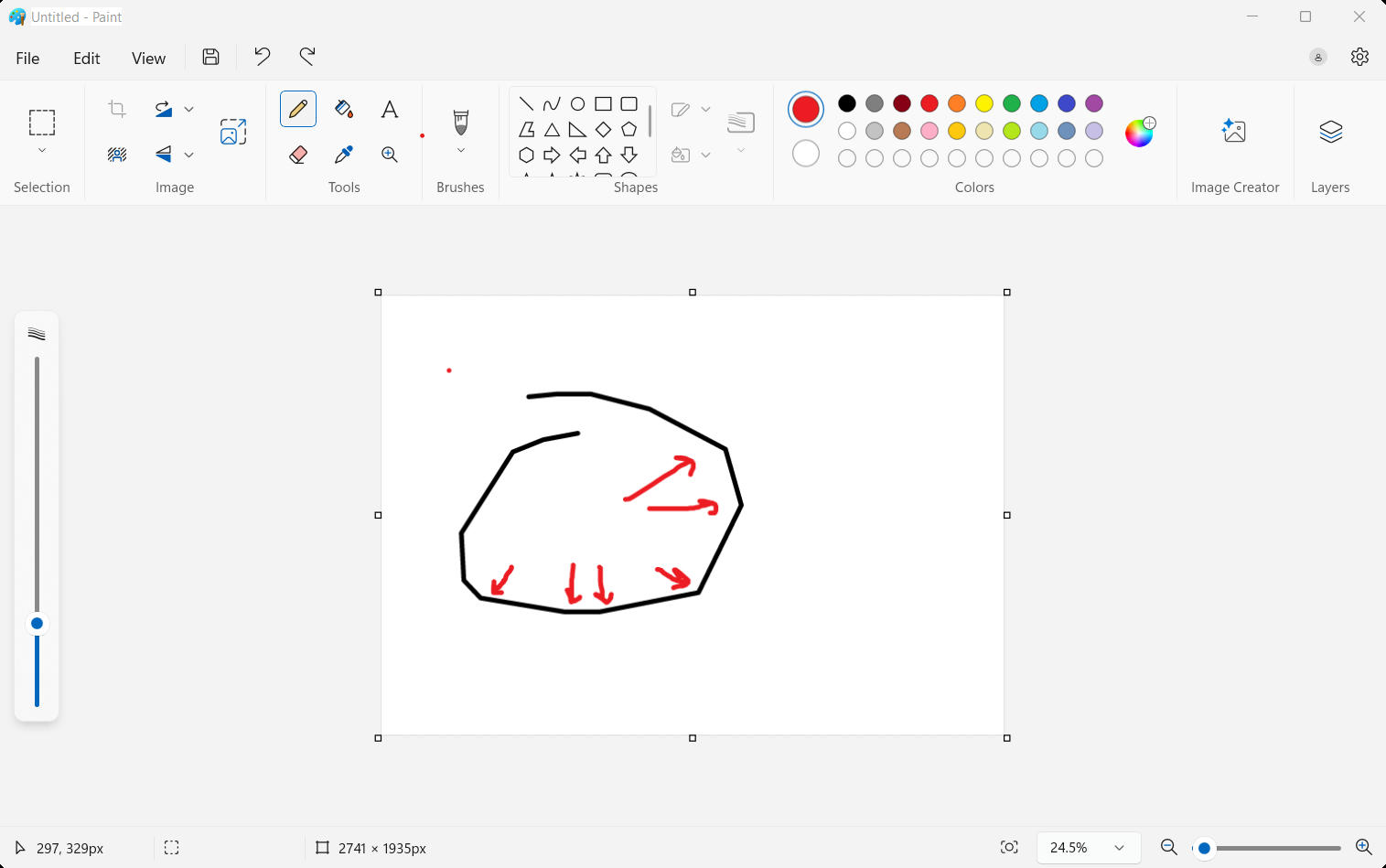

- MS-Paint is relatively ergonomic for simple drawing, but it has a clumsy interface in other ways (1), lacks several fundamental features (namely transparency and magic wand) (2), and only runs on Windows (3).

- Paint.NET was my editor of choice on Windows, but doesn’t run natively on Linux (3).

- Photoshop is not free, and I don’t think it runs on Linux (3).

Thus I set out to write my own editor, RS-Paint3.

Project Nature

This is officially the biggest project I’ve written. It’s 12k LoC.

Much of what I wrote was relatively straight-forward, allowing bursts of very rapid development. This was really satisfying, and It’s helped me better understand why people like web development and ui-coding (and other high-volume, low-effort tasks).

Another curious aspect of this project is that there was virtually no completion criteria, and the minimal functionality was laid out very early on. This made the development process revolve around adding and improving rather than solely implementing a giant skeleton4. This has a vastly different feel, and it was refreshing.

One thing that arose from this (combined with the other logistics of this project (namely rust and GTK)) was a large volume of sub-ideal (“hacked”) solutions. This project opened my eyes to how there is little use in avoiding these.

Design Choices

I would probably describe the look/feel of RS-Paint as “based” (if I’m being generous), and “unpolished” (if I’m being realistic).

My justification for leaving it in such an unrefined state is that “less is more”; modern UIs can easily become over-polished, favoring prettiness over functionality. I value intuition and ergonomics much more than I do appearance, and that’s why I prefer a “based” UI.

But the real reason why the UI is so unpolished is that I dread the process of visual refinment5.

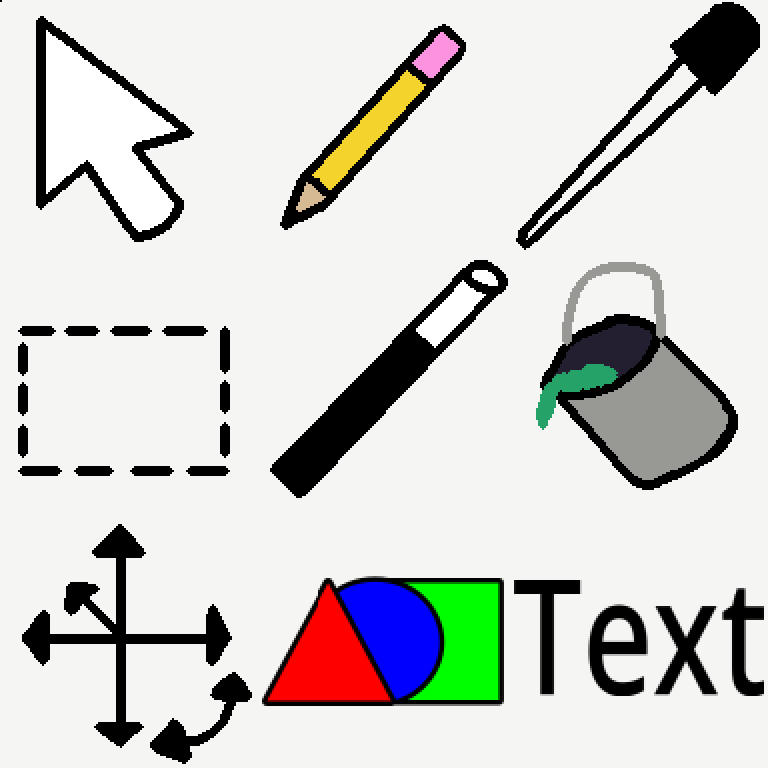

Icons

All icons in RS-Paint are “bootstrapped”, meaning that they were made entirely using RS-Paint. I bet you never would have guessed.

When designing these, my primary goal was intuition: the icon should explain exactly what the tool does (the user should never be confused when searching for a tool).

Jokes aside, it’s amazing how many popular programs have incomprehensible icons.

Here are gimp6’s icons. I challenge you to explain the functionality (or even just say the name) of half of them7.

![]()

Free Transform

Free-transform in RS-Paint behaves in a slightly different way than you might expect.

Most image editors automatically do the following:

- “transfer a selection into free-transform mode”

- “commit the transformed selection”

RS-Paint makes the user explicitly do both of these8.

This only impacts tools that interact with free-transform in some way:

- Selection Tools

- Rectangle Select

- Magic Wand

- Creation Tools

- Shape

- Text

Selection tools are solely for selection: in order to transform the selection, the user must switch to the free transform tool. When the free-transform tool is switched to, the active selection is “consumed” (deleted off of the image). It can then be freely transformed and “committed (and kept)” (re-drawn/rasterized) back to the image, then finally “scrapped” (deleting the transformation selection). The “commit” button is just shorthand for “commit and keep”, then “scrap”.

Creation tools follow a similar pattern: the creation tool is used solely for creating the thing-to-be-transformed; the free-transform-tool must first be switched to (either automatically or manually) to do the actual transforming.

The text tool uses a dialog9 to allow modification during transformation.

Problems : Solutions : Commentary

Here I’ll discuss some of the more interesting problems/challenges I faced throughout development. I’ll order them in nonincreasing order with respect to the key:

actual_complexity * (1.0 / expected_complexity)

That is, the most complex (especially the unexpectedly complex) will come first10.

Image Storage, Layering, Undo

It turns out that all of the following are inherently interweaved.

- Storing and updating the image (as the user modifies it)

- Maintaining multiple layers

- Maintaining the image’s history

- Drawing the image efficiently

(4) is probably the least obvious. It turns out that cairo (the drawing library I used) must be given its images-to-draw in a particular format. For efficiency, we’d like that format to line up exactly with how we natively store the image so a raw pointer can be given to cairo to avoid conversion on every draw11. But the format it demands (pre-multiplied alpha) is seriously undesirable12 as a native image format.

The solution is to maintain two image structs: one regular Image (to be read and written as normal), and one DrawableImage to be directly given to cairo.

The two can then be wrapped in a FusedImage, which forwards writes to both the Image and DrawableImage.

Adding layers is a matter of having an Image and DrawableImage per ever layer, and adding machinery into TrackedLayeredImage that handles the lazy blending of pixels into the global DrawableImage.

This machinery is intertwined with change-tracking code that allows for undo-saves (more on undo later).

The resulting code:

pub struct Pixel {

// the order of the fields is in the unsafe cast in Image::to_file

r: u8, g: u8, b: u8, a: u8,

}

pub struct DrawablePixel {

// order of the fields corresponds to cairo::Format::ARgb32

// (this struct is used for directly rendering the cairo pattern)

b: u8, g: u8, r: u8, a: u8,

}

pub struct Image {

pixels: Vec<Pixel>,

width: usize,

height: usize,

}

pub struct DrawableImage {

pixels: Vec<DrawablePixel>,

width: usize,

height: usize,

}

pub struct LayerProps {

layer_name: String,

locked: bool,

visible: bool,

}

struct Layer {

image: Image,

props: LayerProps,

}

pub struct FusedLayer {

image: Image,

drawable: DrawableImage,

props: LayerProps,

}

pub enum LayerIndex {

BaseLayer, // The bottom layer

Nth(usize), // The (n + 1)'th from bottom layer (0 = first from bottom)

}

pub struct FusedLayeredImage {

drawable: DrawableImage,

base_layer: FusedLayer,

/// Non-base layers, increasing in height

other_layers: Vec<FusedLayer>,

active_layer_index: LayerIndex,

// Only one layer is active at a time:

// the below keep track of changes made to

// the currently-active layer

pix_modified_since_draw: HashMap<usize, Pixel>,

pix_modified_since_save: HashMap<usize, (Pixel, Pixel)>,

}

/// An interface of `FusedLayeredImage` that only exposes

/// undoable operations (used by `DoableAction`)

pub trait TrackedLayeredImage {

fn pix_at(&self, r: i32, c: i32) -> &Pixel;

fn pix_at_mut(&mut self, r: i32, c: i32) -> &mut Pixel;

fn try_pix_at(&self, r: i32, c: i32) -> Option<&Pixel>;

fn try_pix_at_mut(&mut self, r: i32, c: i32) -> Option<&mut Pixel>;

fn width(&self) -> i32;

fn height(&self) -> i32;

}

The pix_modified_since_draw and pix_modified_since_save hash-maps are used for lazily updating the drawable and lazily accumulating changes, respectively.

pix_modified_since_draw is populated on calls to [try_]pix_at_mut, and pix_modified_since_save is populated when pix_modified_since_draw is flushed (in the accessor to drawable).

This is one many possible schemes for accomplishing the same result.

This particular arrangement is good at avoiding unnecessary computations (because of its laziness).

Drawing

Given a set of points that the cursor followed, create a smooth path across those points, and rasterize that path.

The two core difficulties here are:

- Path creation

- Rasterization

(1) is hard because the input path is, in pathological cases, jagged (the sampling rate is never fast enough to track the sufficiently fast user’s cursor, so the resulting point-trace ends up being un-rounded).

One possible solution is to ignore the problem and live with the jagged edges (MS-Paint does this).

The other approach is to assume that quickly-drawn strokes are probably meant to be round, and to take the given points and compute a smooth curve that connects them. Splines are the mathematical formula to approximate a polynomial connecting several points, so they’re a natural solution to this problem. The drawback is that more than two points are needed to draw a non-linear spline, and waiting for a third point adds a bit of a lag to the display of the line.

Some programs address this by first rendering the jagged line, then, upon release (when the stroke is “committed”), the jagged line is replaced by the smoothed one. I prefer the (very slight) lag over the re-render, so I chose to keep it.

(2) is a little more obvious: given the formula for the curve, how do we draw it onto the image? This naturally leads to the question: “what is a brush?”

I chose the maximally trivial definition: “a brush is an image”. And therefore strokes are rasterized via periodic sampling (that is, the brush-image is drawn at evenly-spaced points along the curve). The spacing of the samples is slightly scaled up as the size of the brush increases (to avoid especially slow performance on big brushes).

This sampling strategy leads to brush-samples being drawn on top of each other (or at least partially overlapping). When the color we’re drawing is transparent, this causes the overlapping parts of the samples to be darker. To fix this, we can keep a mask of drawn-on-pixels for each stroke, and prevent re-drawing pixels we’ve already touched.

The possibility for (semi-)transparent strokes brings up another issue with rasterization: how should transparent colors be blended? For example, consider a fully transparent pencil stroke. There are at least two potential interpretations:

- The stroke should clear out all opaque pixels in its path

- The stroke is transparent, and should have no effect

Neither interpretation is wholly correct, so to support both, we’ll add the notion of “blending modes”.

- Overwrite: the color of drawn pixels replaces the old color

- Paint: the color of the drawn pixel is “blended onto” the old color, with respect to transparency; this is the same as as

Overwritewhen the new pixel is opaque - Average: all color channels of the drawn color and old color are averaged

The allowance of transparency as “a valid color” (in the Overwrite blending-mode) causes a problem with the definition of a brush as “just an image”: we need a new notion of “absence of color” other than transparency (else transparent brushes cannot have non-rectangle shape).

The following definition results.

pub struct BrushImage {

pixel_options: Vec<Option<Pixel>>,

width: usize,

height: usize,

}

Multi-Level Undo

Ever since watching this legendary talk by Sean Parent I’ve been itching to implement multi-undo. This project poses the perfect opportunity to do so in a non-trivial context.

My implementation is about as vanilla as it gets. I toyed with using some sort of immutable trie-like data structure13, but it turned out to be a lot tricker than I expected, and I gave up quickly. I ended up using a tree of diffs. Getting everything to line up is a little tricky, because nodes of the tree represent diffs, not states, but it’s otherwise straight-forward.

struct UndoNode {

parent: Option<Weak<UndoNode>>,

children: RefCell<Vec<Rc<UndoNode>>>,

recent_child_idx: RefCell<usize>, // index of the most recently visited child

value: Rc<RefCell<ImageStateDiff>>,

// below is gui-related

widget: gtk::Box,

label: Label,

button: Button,

container: Rc<gtk::Box>, // possibly inherited from parent

}

The implementation is a little verbose because pointer-based trees are annoying in Rust.

If you don’t know Rust, ignore every instance of Weak, Rc, and RefCell, and pretend it’s Java.

Undo involves moving upward into the parent; redo downward (into recent_child_idx).

Traversing to a specific commit involves finding a least-common-ancestor (I naively used bfs to do this), then applying (or unapplying) the diffs, in order, along the path.

Layers (namely the currently active layer) also have to be tracked by undo. All operations that impact layers (reorders, merges, clones, layer creation) must be logged as undo actions. Single-layer modifications (which act on the currently-active-layer) must be constrained to not resize the image, and all resizing operations must operate on all layers.

Many diffs are manually implemented (for time and space efficiency), but automatic change tracking is possible too (see the section on image storage for more on this).

There are a variety of “...Action” structures/traits that allow wrapping code with a variety of different change-allowing APIs.

/// An action that uses the automatic undo/redo in `FusedLayeredImage`

/// (exposed through the `TrackedLayeredImage` interface)

pub trait AutoDiffAction {

fn name(&self) -> ActionName;

fn exec(self, image: &mut impl TrackedLayeredImage);

// undo is imlpicit: it will be done by diffing the image

}

/// An action with a manual undo that modifies the image

/// through the `ImageLikeUncheckedMut` interface. The action

/// will only be used on a single layer (and is free to store

/// mutable data tied to that layer).

pub trait SingleLayerAction<I>

where I: ImageLikeUncheckedMut

{

fn name(&self) -> ActionName;

fn exec(&mut self, image: &mut I);

fn undo(&mut self, image: &mut I); // explicit undo provided

}

/// An action with a manual undo that is given full access

/// to the `Image` (including resizing). The action is

/// executed/undone to each layer individually.

/// It's assumed that both `undo` and `exec` are effectively

/// pure in terms of the size of the input and output image (so

/// layers sizes will not become mismatched).

pub trait MultiLayerAction {

/// Layer-Specific undo data provided mutably to both

/// `exec` and `undo`

type LayerData;

fn new_layer_data(&self, image: &mut Image) -> Self::LayerData;

fn name(&self) -> ActionName;

fn exec(&mut self, layer_data: &mut Self::LayerData, image: &mut Image);

fn undo(&mut self, layer_data: &mut Self::LayerData, image: &mut Image);

}

Every type of history-changing (undoing/redoing/traversing) is an application of diffs which change the entire FusedLayeredImage.

This means that the DrawableImages must also be updated.

The two naive ways to do this are inefficient in their respective pathological cases:

- Update all changed pixels/layers, as applied. (inefficient when a large chain of diffs is applied and the intermediate drawable-changes are overwritten before the drawable is rendered)

- Update all layers, once at the end. (inefficient when a single-layer change is applied to a many-layer image)

My solution is to accumulate (but not apply) all changes (to the drawables) when the diffs are applied, then to apply the accumulated changes once at the end. Layering makes this a little hairy, because rearranging of layers, mid-accumulation, must be accounted for.

/// Specifies which drawables/pixels of

/// a `FusedLayeredImage` should be re-computed. This

/// can be used to lazily accumulate changes before updating.

/// The inclusion of any pixel implicitly includes that

/// pixel on the "main-drawable" (`FusedLayerImage::drawable`).

struct DrawablesToUpdate {

full_layers: HashSet<LayerIndex>,

/// pixels_in_layers[i] <=> set of flat indices into LayerIndex::from_usize(i)

pixels_in_layers: Vec<HashSet<usize>>,

/// If this is `true`, the main drawable will always be updated.

/// If not, it will be updated if any full layer is included;

/// if none are, it'll be updated at any pixels in `pixels_in_layers`.

definitely_main: bool,

}

Bitmask Outlining

The drawing of a bitmask’s outline (and filling the selected area) is yet another non-trivial problem.

Luckily, I was able to ride off cairo’s back14 for most of the geometric calculations (in this case, the fill15). But cairo never does all of the work.

The outline alone isn’t too bad: just look at every pixel and check its borders. Unfortunately, cairo isn’t able to fill a path (shape) that’s assembled with the border segments in arbitrary order.

So I used a relatively straight-forward algorithm to, given a bitmask, find the outline (list of points, connected by grid-aligned segments) each distinct “shape”.

- Find each segment by scanning each row and column and checking for boundaries

- Place the segments into hash maps so they can be looked up by their endpoints

- Start from an arbitrary endpoint of an arbitrary segment, and repeatedly explore unvisited segments that end at the same point

- Repeat this for each “strongly connected component” (shape) of segments in the bitmask (until there are no unvisited segments)

- The order in which the segments were visited is the order they should be traced in cairo to allow for filling

(see image::bitmask::ImageBitmask::gen_edge_path for the full code)

This algorithm might fall apart when given pathological bitmasks (e.g. ones with dithered selection), but since all brushes and magic-wand-selections form “nice” shapes, I haven’t ran into any problems with it.

If it were a little less sloppy, it would probably make a good leetcode problem.

Free Transform

I dreaded this problem for a long time, and put it off so it was one of the last tools I implemented.

It turned out to be quite fun16 to solve, because my insistance on generality exposed the core of the problem, leading to a relatively simple solution.

The idea was that free-transform should work on all of the following:

- Rectanglular Images

- Image Bitmasks

- Shapes

- Text

(1) and (2) were later combined, but that fact is irrelevant.

So what’s the least common denominator of all of these things (that is necessary for free transform)?

- Sampling: look up a pixel value at a given coordinate17 (used for rasterization)

- Drawing (display the thing with cairo; kept sepearte for efficiency)

pub trait Samplable {

/// Get a pixel value at given (x, y)

/// (coords should be in the unit square)

fn sample(&self, x: f64, y: f64) -> Pixel;

}

pub trait Transformable {

/// Draw the untransformed thing within the unit square: (0.0, 0.0) (1.0, 1.0)

fn draw(&mut self, cr: &cairo::Context, pixel_width: f64, pixel_height: f64);

fn gen_sampleable(&mut self, pixel_width: f64, pixel_height: f64) -> Box<dyn Samplable>;

// (this was later added to allow for different scaling algorithms of selections)

fn try_image_ref(&self) -> Option<&Image>;

}

gen_sampleable18 is used instead of an accessor because the underlying data might not be inherently sampleable (and might need extra computation).

From here, it’s a matter of simultaneously maintaining translation, scale, and rotation of the transformation, displaying the transformed result, and modifying it with respect to its current transformation.

It’s amazing how easy this sounds if you know the trick and how difficult it sounds if you don’t19.

This trick is the transformation matrix, which (in a nutshell) maintains those three things (translation, scale, and rotation), and makes them easy to apply, invert, and combine (with other matrices).

The implementation also required a few hundred lines of geometry logistics for…

- Determining “what the cursor should do” (translate? scale? (which direction?) rotate?) based on its position relative to the transformation

- Calculating the correct amounts to translate/scale/rotate to (independently)…

- Clamp the transformation to the grid

- Maintain the aspect ratio of the transformation

- Draw the free-transform UI thing (the box around the transformation, the points on the corners, etc.)

Shapes and Text

I expected the implementation of gen_sampleable for shapes and text to be tricky.

For shapes it would be a matter of maintaining a vector-image (which I have no clue how to do), or doing the math to determine if a given point’s distance from a line segment20 (perhaps they’re isomorphic).

For text, I would have to find some tool to render a given font as a vector image, then do a point lookup (sample) on that image.

Luckily, I had a tool at my fingertips that could roughly do both: cairo. I was a little hesitant to do this at first (because it feels a little too much like a hack), but I eventually decided that there’s no21 shame in the hack, so long as it works well22.

So with a handful of lines, I added a default implementation of gen_sampleable that rode off the back of cairo to make a Samplable solely by using the draw method.

This made implementing both shapes and text as easy as23 implenting draw (to draw the thing to a cairo context).

pub trait Transformable {

fn draw(&mut self, cr: &cairo::Context, pixel_width: f64, pixel_height: f64);

fn gen_sampleable(&mut self, pixel_width: f64, pixel_height: f64) -> Box<dyn crate::transformable::Samplable> {

// default implementation: ride off the back of cairo,

// use the `draw` method, then sample off of the resulting context

let width = pixel_width.ceil() as usize;

let height = pixel_height.ceil() as usize;

let surface = cairo::ImageSurface::create(

cairo::Format::ARgb32,

width as i32,

height as i32,

).unwrap();

let cr = cairo::Context::new(&surface).unwrap();

cr.scale(pixel_width, pixel_height);

self.draw(&cr, pixel_width, pixel_height);

std::mem::drop(cr);

let raw_data = surface.take_data().unwrap();

let drawable_image = DrawableImage::from_raw_data(width, height, raw_data);

Box::new(drawable_image)

}

fn try_image_ref(&self) -> Option<&Image> { None }

}

Design Patterns in the Wild

Since my post on design patterns, I decided to be on the lookout for patterns that naturally arose in this project. Here’s what I noticed:

Builder, Iterator

Both of these are used all over in Rust. There probably isn’t a file in this project that doesn’t use one or the other. I feel like they’ve (especially iterator) transcended the status of “design patterns”. The term “idiom” feels more accurate.

Mediator

GTK widgets are assembled all over this program; to facilitate this, I made wrapper structures called Fields, which wrap GTK widgets to simplify their interface (this isn’t the mediator part: it could probably be described as a facade).

Fields could then be wrapped in Forms (just wrappers for GTK containers).

There were a few common patterns of bundled-together Fields interacting.

One example of this is the “lock-aspect-ratio” input (a height and width field with a checkbox to lock the aspect ratio).

To allow for re-use of such functionality, I created the notion of Gadgets, which serve as mediators between Fields.

pub trait FormBuilderIsh {

fn with_field(self, new_field: &impl FormField) -> Self;

fn with_focused_field(self, new_field: &impl FormField) -> Self;

}

pub struct Form {

widget: gtk::Box,

}

pub struct FlowForm {

widget: gtk::FlowBox,

}

pub trait FormField {

fn outer_widget(&self) -> &impl IsA<gtk::Widget>;

}

trait FormGadget {

fn add_to_builder<T: FormBuilderIsh>(&self, builder: T) -> T;

}

pub struct AspectRatioGadget {

old_width: usize,

old_height: usize,

enforce: bool,

width_field: NaturalField,

height_field: NaturalField,

ratio_button: CheckboxField,

}

impl FormGadget for AspectRatioGadget {

fn add_to_builder<T: FormBuilderIsh>(&self, builder: T) -> T {

builder

.with_field(&self.width_field)

.with_field(&self.height_field)

.with_field(&self.ratio_button)

}

}

impl AspectRatioGadget {

fn update_ratio(&mut self) {

self.old_width = self.width_field.value();

self.old_height = self.height_field.value();

}

pub fn new_p(

width_label: &str,

height_label: &str,

default_width: usize,

default_height: usize,

allow_zero: bool,

) -> Rc<RefCell<Self>> {

let state_p = Rc::new(RefCell::new(AspectRatioGadget { /* ... */ }));

// set up hooks that reference the mediator (state_p)

state_p.borrow().ratio_button.set_toggled_hook(clone!(@strong state_p => move |now_active| {

state_p.borrow_mut().enforce = now_active;

if now_active {

state_p.borrow_mut().update_ratio();

}

}));

state_p.borrow().width_field.set_changed_hook(clone!(@strong state_p => move |new_width| {

if let Ok(state) = state_p.try_borrow_mut() {

if !state.enforce { return }

let width_change = new_width as f64 / (state.old_width as f64);

state.height_field.set_value((state.old_height as f64 * width_change).ceil() as usize);

}

}));

state_p.borrow().height_field.set_changed_hook(clone!(@strong state_p => move |new_height| {

if let Ok(state) = state_p.try_borrow_mut() {

if !state.enforce { return }

let height_change = new_height as f64 / (state.old_height as f64);

state.width_field.set_value((state.old_width as f64 * height_change).ceil() as usize);

}

}));

state_p

}

pub fn width(&self) -> usize {

self.width_field.value()

}

pub fn height(&self) -> usize {

self.height_field.value()

}

}

Command

Actions (which associate undoable code with a struct (see above)) are commands.

Facade

As mentioned above, in order to prevent the pencil tool re-blending of the same pixel in the same stroke, a hash-map of modified pixels is kept, and reset at the end of each stroke. The hash map isn’t actually “reset” (cleared), though; instead a counter is incremented (which is much more efficient). The API maintains the facade that a hash map is being cleared (by naming the method clear_pencil_mask) (since that’s easier to understand).

pub struct Canvas {

/* ... */

/// A mask corresponding to the flattened image pixel

/// vector: `pencil_mask[i]` == `pencil_mask_counter`

/// iff the pixel at index `i` has been drawn on

/// during the current pencil stroke

pencil_mask: Vec<usize>,

pencil_mask_counter: usize,

/* ... */

}

impl Canvas {

fn test_pencil_mask_at(&mut self, r: usize, c: usize) -> bool { /* ... */ }

fn set_pencil_mask_at(&mut self, r: usize, c: usize) { /* ... */ }

pub fn clear_pencil_mask(&mut self) {

self.pencil_mask_counter += 1

}

}

Adapter/Proxy/Facade

I used the arboard crate for managing the system clipboard.

It has a Clipboard struct with get_image and set_image methods.

I liked this interface, but didn’t want to directly use it in my “business-logic” code because it’s pretty low-level, so I wrote my own Clipboard struct with a similar interface that wraps a arboard::Clipboard and accepts my higher-level Image type.

/// Wrapper for arboard::Clipboard; using the wrapper

/// to make it easiser to tweak the api/ add side-effects

/// (facade pattern)

/// Fails gracefully when the clipboard is unavailable.

pub struct Clipboard {

clipboard: Option<arboard::Clipboard>,

// this is necessary because the system clipboard doesn't own its image data

// (it references this instead)

copied_image: Option<Image>,

}

impl Clipboard {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let clipboard = arboard::Clipboard::new()

.map(|c| Some(c))

.unwrap_or(None);

if clipboard.is_none() {

eprintln!("Failed to load clipboard");

}

Clipboard {

clipboard,

copied_image: None,

}

}

pub fn get_image(&mut self) -> Option<Image> {

self.clipboard.as_mut().and_then(|clipboard| { // only do this if self.clipboard is Some(..)

if let Ok(image_data) = clipboard.get_image() {

// make an `Image` from the `image_data`

} else {

None

}

})

}

pub fn set_image(&mut self, image: Image) {

self.clipboard.as_mut().map(|clipboard| { // only do this if self.clipboard is Some(..)

let image_data = arboard::ImageData { /* construct this from `image` */ };

let _ = clipboard.set_image(image_data);

});

}

}

Observer

The observer pattern is built into GTK and used all over through connect_... methods.

This is the way button clicks (and virtually any other UI event) are handled.

Momento

It’s questionable if this counts as a momento, but LayeredImage is serialized as the “project file”.

Rust

This is my first major24 project using Rust25. I learned a lot and developed a lot of opinions throughout the process. The following are some of them.

Learnings

Borrow Checking, Basic Semantics (All Hail The LSP)

I think that some degree of eager learning is desirable for Rust26 (I read the book, and I’m glad I did), but, as with most languages, true understanding only comes from using the thing.

I owe the speed of my understanding of the Rust’s ubiquitous mechanics of Rust to the tight feedback loop of my LSP and IDE.

And the faster you receive feedback from your IDE, the faster you can learn how to use the language.27 In almost no time at all, you’ll be anticipating what the red underline means before the error text even appears. Soon after that, the you’ll be anticipating a red underline before it even shows up. This same process happens when you wait for compilation for feedback, but it takes much longer.

You can imagine the shrinking of the feedback loop as technology progresses.

- Punch Cards (wait for the operator to hand you the results)

- Teletype (wait for the terminal to type the result)

- Terminal Emulator (wait until you’re ready to compile to see the results)

- Modern IDEs (receive the results as you type)

Each step is quite substantial. Ignoring the last one is naive.

It’s hard to imagine what might be next.

Interior Mutibility

I finally figured out what Rc and RefCell do (after being seriously perplexed when I first saw them28, then the next hundred times I saw them).

Rc<T> is a immutable reference-counting pointer.

It’s immutable in the sense that you’re not allowed to mutably borrow the T (only immutable borrows are allowed).

Cloning the pointer is allowed, and doing so copies the address and increments the reference count.

RefCell<T> isn’t a pointer at all; it’s a “mutable memory location with dynamically checked borrow rules”.

This means two things:

- You can mutate the

T(get a&mut T) when you only have immutable access to theRefCell(a&RefCell<T>) - Doing so will cause a run-time panic if

Tis (or becomes) borrowed anywhere else

Cloning a RefCell<T> is only allowed if the T can be cloned, and the clone will be a new memory location.

This is because (again) RefCell<T> is not a pointer; it’s much like holding onto a T, just with these special borrowing rules.

Rc and RefCell are often used together (as Rc<RefCell<T>) because their combined behavior is a clonable pointer with interior mutability (which mirrors the behavior of pointers in virtually every other popular modern language).

Since Rc<T> implements Deref<Target = T>, methods of &T can be directly used on the Rc<T>, and therefore methods of RefCell<T> can be used on Rc<RefCell<T>>.

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

let seven: Rc<i32> = Rc::new(7);

{

let same_seven = Rc::clone(&seven); // points to the same memory location;

// the reference count is incremented to 2

} // `same_seven` is dropped, the reference count is decremented to 1

let num: RefCell<i32> = RefCell::new(1); // note that `num` is NOT declared as mutable...

// ... despite this, we can still change its internal value

*num.borrow_mut() = 2;

println!("{}", num.borrow()); // => 2

// but `num` is not a pointer, so we can't have shared ownership of it;

// cloning works, but makes a "deep copy"

let num_clone = num.clone(); // `num_clone` is an entirely different memory location

*num.borrow_mut() = 3;

println!("{}", num_clone.borrow()); // => 2

// to make a "shallow copy", we need to wrap the RefCell in a Rc

let num2: Rc<RefCell<i32>> = Rc::new(RefCell::new(4));

let num2_clone = Rc::clone(&num2);

// borrow_mut() is a method on RefCell; this call works, because

// Rc<RefCell<T> can dereference into RefCell<T>

*num2.borrow_mut() = 5;

println!("{}", num2_clone.borrow()); // => 5

} // the reference counts of `seven` and (`num2`/`num2_clone`) are decremented to 0, the memory is freed

Lifetimes

When trying to eagerly learn Rust, I found lifetimes elusive. I think (much like monads and other similarly complex topics) that they’re best understood when you’re forced (or encouraged) to use them in context29.

The situation when I most often reached for lifetimes (besides 'static) was when I wanted to use a reference in a struct.

Doing so is not allowed without explicit lifetimes.

pub struct SampleableCommit<'s, 'i> {

sampleable: &'s dyn Samplable,

matrix: cairo::Matrix,

scale_method: ScaleMethod,

image_option: Option<&'i Image>,

culprit: ActionName,

}

impl<'s, 'i> AutoDiffAction for SampleableCommit<'s, 'i> {

fn name(&self) -> ActionName { /* ... */ }

fn exec(self, image: &mut impl crate::image::TrackedLayeredImage) { /* ... */ }

}

// code that uses `SampleableCommmit` (simplified)

fn commit_transformable_no_update(&mut self) {

let selection = /* ... */; // 'i begins (the `Image` is stored somewhere within `selection`)

let sampleable = selection.transformable.gen_sampleable(width, height); // 's begins

let commit_struct = SampleableCommit::new(

&*sampleable, // pass in 's

selection.matrix,

self.ui_p.borrow().toolbar_p.borrow().get_free_transform_scale_method(),

selection.transformable.try_image_ref(), // pass in 'i

selection.culprit.clone(),

);

// consumes `commit_struct` ('s and 'i both alive, so this is fine)

self.image_hist.exec_doable_action_taking_blame(commit_struct);

// 's and 'i end

}

For example, the above struct (SampleableCommit) is used to draw a Samplable to the image.

We want to wrap up all of the information necessary for drawing into a single struct (to allow it to implement AutoDiffAction), yet we don’t want to clone the Sampleable and the Image (in this case, we couldn’t even if we wanted to30).

Since we know that the SampleableCommit struct will be dropped before the Sampleable and Image ('s and 'i), there’s no reason we can’t wrap the references into a struct.

The lifetimes are how we express this to the compiler.

Opinions

Haskell-ish-ness (or, Multi-Paradigm spread)

It’s insane how close Rust comes to Haskell considering how low-level it is. As much as I love Haskell, I’ll be the first to admit it isn’t practical. I now view Rust as a viable practical replacement for Haskell.

Obviously there are many differences, but they’re similar in most of the important ways. The key point is that, using Rust, I can solve problems in mostly the same way31 that I solve them in Haskell.

The same cannot be said about Java or C++ (even when they technically offer the ability to do something haskell-ish, they never feel32 like Haskell). And while you might argue this is theoretically true for Python, or perhaps even JavaScript, the feel is considerably different because of their dynamic typing and the lack of ADTs and traits/generics that results.

Rust feels like Haskell because Rust is designed to make functional-style natural (via these features):

- Algebraic Data Types

- Iterators

- Immutability by default

- Closures, first-class functions

- Traits

- Generics

But often the functional approach is sub-ideal33. In these cases, Rust makes it (almost) just as easy to use the imperative approach.

That’s the appeal of multi-paradigm languages, and Rust seems to do it right34.

Fun / Satisfying / Easy / Safe / Fast

There are a lot of language features in Rust that simply feel good to use. They’re the type of thing that, when coding with other languages, I say “if I were coding in Rust, I could just do it like this”. The following is a non-exhaustive list of such features.

All blocks are expressions: this is something you don’t realize you need until you have to live without it. Which of the following C++ snippets is better?

// (1) "return out of the if-block"

int f(int x) {

if(a) {

return A;

} else if(b) {

return B;

} else {

return C;

}

}

// (2) "set a variable"

int f(int x) {

int result;

if(a) {

result = A;

} else if(b) {

result = B;

} else {

result = C;

}

return result;

}

(1) is arguably less extensible, because the if-else-block is inherently tied to the function (due to the inner-returns in each clause), and it relies on being the only statement in the function body.

(2) isn’t great either, because it…

- Unnecessarily introduces a new variable (

result)- Add another name to the soup

- Adds a dimension of complexity (mutation of that variable)

- Opens the possibility that a clause might forget to assign to

result(this is actually true in both cases, but it’s easier to assert that a block returns than to assert that it assigns a variable) - Introduces a sentinel value (likely

null, or garbage) thatresultmust first be assigned to

Compare this to the solution in Rust:

fn f(x: i32) -> i32 {

/* let result = */ if a {

A

} else if b {

B

} else {

C

} /* ; */

}

The default behavior is to return the last (un-semicolon’d) expression in the block. This applies to both the if-else-block and the function block, so we get our desired behavior with a lot less syntax. Furthermore, extending the function body (while ensuring each block “returns” something, of the same type) is as simple as uncommenting the above code (placing the if-else expression into a let statement).

This all-blocks-are-expressions property also allows a few other nice conventions {

No Ternary Operator: use

if x { y } else { z }

…instead of…

x ? y : z

(this is more easily extendable)

Long computations can be scoped away:

let x = {

/* some long and complex computation, assigning to many variables */

result

};

}.

ADTs are native and natural:

“Native”: sum types (enums) and product-types (tuples) are possible to represent using the core language without excess machinery.

“Natural”: the language provides features to (greatly) facilitate their use:

- Pattern Matching (

match)- Even numeric ranges too!

- Tuple unwrapping within function parameters

- If-let

?

The borrow checker (when it agrees with what you’re trying to do) feels effortless and fun. It’s hard to explain this with an example, so here’s an anecdote instead: when I went back to coding in other languages after this project, I was so accustomed to Rust that I had a hard time thinking outside of “moves” and “borrows”. Though it’s tricky to pick up, once you do, there’s something very natural about this way of thinking.

Verbosity is minimal, without being confusing:

Just look at the keywords: fn, pub, use, mod, struct, trait…

The built-in types are also very nice:

- Numeric types: (

i32,u8,usize, …) - Containers: (

Vec<T>,HashMap<T>, …)

The code formatting standards liberally use line breaks. This might seem a little trivial, but this makes editing code considerably easier (and version-control diffs nicer). It also pads my LoC count.

The built-in traits (and trait system in general) are easy to use.

derive usually “just works”.

Using generics in impl-blocks is really cool (did I mention it feels like Haskell?).

The built-in traits allow the user to specify the behavior of built-in (language-level35) operators/conventions (e.g. formatting).

Drawbacks

That being said, Rust isn’t solely a joy to work with. I think the positives outweigh the negatives, but there are still negatives:

- fighting the type system

- borrow checking is sometimes annoying (have to add an extra block or manual drop)

Rc<RefCell<T>>can be a pain (panics…)- often dealing with references is a little annoying (you have to dereference even value types)

- macros (though seemingly nice), often have clumsy results, and by nature aren’t easy to use (in non-trivial cases)

GTK

GTK is the GUI library I used. It turned out to be a little less nice to work with than expected. This was primarily because GTK is a C library36 (not natively written in Rust, and therefore lacking the Rustic conventions I’m so fond of). The bindings do what they can, but it’s hard to have a complete facade, and the C starts to seep in at the seams.

GTK is also part of an overarching glib ecosystem, which means that doing certain operations requires digging into other libraries (glib, gio, gdk, and pango, to name a few).

This isn’t terrible, but it’s a little less cohesive than it could be.

Some aspects of GTK are really convenient (like the built-in dialogues for the about-screen and keyboard-shortcuts),

others are perplexing (like the necessity to create a ListStore to supply approved filetypes),

and others straight up annoying (like the deprecation of FontChooser without replacement, and the apparent impossibility to do certain low-level things (like listen for certain events)).

There were many sketchy (hacked) work-arounds I had to write when GTK didn’t do quite what I wanted.

GTK widgets heavily use interior mutability (passing references to them often means implicitly passing ownership to a (mutable) pointer). This causes some odd semantics and questions of ownership (reference counted? garbage collected?) (that I mostly ignored). For example:

{

let wrapper = gtk::Box::builder()

.orientation(gtk::Orientation::Horizontal)

.spacing(4)

.build();

// creating and passing in a reference to a new Label

wrapper.append(>k::Label::new(Some("Justification:")));

// the `Label` is dropped, but still held by `wrapper`

}

GTK allows/encourages the use of CSS; I shunned it for a while, but it’s actually pretty nice to use37.

There’s also apparently a .ui file format that can be used to specify entire layouts, but I never tried to do that.

Overall, GTK does the job, but I’d certainly consider other alternatives before using it again. A lot of the low-level stuff could definitely be improved. The rest is questionable: perhaps UIs are sufficiently complicated that it’s infeasible to both idiomatically and cleanly code one using Rust’s conventions (like Haskell).

Romantic Retrospective

This is a program I’ve dreamed of writing for a long time. A program with a big, pretty38 UI. A program that I couldn’t fathom3940 entirely until I sat down and wrote it. A program that I would actually use.

Just a few years ago, I looked at programs like MS-Paint, and was baffled by the fact that made from text41.

Now I’ve written something that I claim is better than (or at least comparable to) MS-Paint.

And now it’s done and the next one begins…

I won’t get into the details of what really qualifies as “ergonomic”, as it’s highly subjective and not a very interesting subject to reason about logically. It’ll suffice to say that I’ve shaped the program to my preferences for UI. ↩︎

Gimp’s UI is notoriously unintuitive, and often involves way more clicks than necessary. Here’s an Eric Murphy video that demonstrates exactly what I mean ↩︎

The name “RS-Paint” is a play on the names of the subpar editors that inspired it. It’s only one letter away from “MS-Paint”, and, like “Paint.NET”, it contains a reference to the tooling that was used to create it (“RS” for “Rust”). Perhaps this isn’t very original, but I figured it more clever than yet another random fake-word or word-play like “imigia” or “photon”, or whatever. ↩︎

“Implementing a giant skeleton” is an accurate description of all of my compiler-related projects (which follow the same skeleton: lex, parse, evaluate). ↩︎

This section perfectly explains the design of my website. ↩︎

Gimp isn’t the exception here: in my experience, most programs’ icons are confusing. Confusion is the norm, simplicity is the exception. ↩︎

You might argue that Gimp’s icons’ meanings are difficult to understand because the things they accomplish are complex (and mine are simple because they have less functionality). This is a fair point, and I’ll concede that it’s acceptable to have complex icons/functionality so long as it doesn’t hamper the intuition of simple operations. The problem with Gimp (and other such programs) is that they destroy simplicity by intertwining simple and complex functionality. They place every-day tools right next to tools the average Joe will never use. It’s not a skill-issue, it’s bad UI. ↩︎

I chose to do it this way because (1) it’s easier to implement (especially when it comes to undo), and (2) it doesn’t make any assumptions about what the user wants. This is arguably a sacrifice of intuition, but I hope that it’s worth the gain in control (it’s hard for me to tell, because I’ve become accustomed to it). ↩︎

This could also be implemented by switching back to the text tool, but I decided the dialog was cleaner. ↩︎

I choose this ordering because I suspect the few people who open this post will likely not get too far (I don’t blame them; I wouldn’t either), so I might as well peak curiosity early on. ↩︎

Which would obviously be incredibly inefficient. ↩︎

This is because color values are stored as integers (one byte per color channel; I chose this arbitrarily, but decided to stick with it for efficiency), so using storing colors with pre-multiplied alpha is pretty lossy. ↩︎

As you’ll soon see, I rely on cairo quite a bit. ↩︎

The fill algorithm used for bitmask is the even-odd rule, which (as I understand) draws a line from any given point outward, then counts the intersections of the shape’s edges to determine if it’s “in the shape” (even), or “out of the shape” (odd). ↩︎

The non-arithmetic parts were fun, at least. ↩︎

Coordinates are relative to the unit square (between the points (0.0, 0.0) and (1.0, 1.0)) for complete generality: shapes and text are effectively vector until they’re rasterized, so it doesn’t make sense to assign them any specific height/width, so we use 1.0. ↩︎

Please forgive the inconsistent spelling of “sampl[e]able”: I still haven’t made up my mind. This is one of the cons of really good autocomplete: it’s easy to ignore a typo. ↩︎

This sentence is the probably one of the strongest arguments for getting a CS degree. Sometimes, it’s useful to have a certain baseline of knowledge, which would otherwise be hard to obtain through lazy learning. I remember thinking that it would be useful to wait to start this project until I took a graphics class (UW’s CS 559). That was generally false, with two major exceptions: (1) this, and (2) splines (see above). ↩︎

Which I learned (from ICPC (training)) is way harder than it sounds. ↩︎

Perhaps “no shame” is a little too strong. There is always some shame, but if the hack is deliberate and calculated, it should be embraced. See my blog on hacking for more on this. ↩︎

So many other parts of this project were already “tainted” (in my POV) by hacking anyway, and I was losing patience, so the hacked option started seeming more and more attractive. ↩︎

There was more code involved in both (neither was “trivial” after this, per se), but no extra work for drawing or sampling. ↩︎

Major = non-trivial ~= >1000 LoC. I would describe my work with Rust before this as “dabbling”. I would now describe Rust as one of my “primary languages”. ↩︎

Ironically, it’s also the biggest project (by LoC) I’ve done, by far (>12K LoC). The second biggest project (APL Interpreter, which was >3500 LoC) was also my first stab at a language (Haskell at that case). I never intended to make this a habit, but it’s proven quite effective. If my next big project isn’t in Rust, it’ll likely be in a language I’ve never used before. ↩︎

The Primagen says something of the same sentiment in this video. ↩︎

I’m probably preaching to the choir to some extent here (basically everybody uses VSCode nowadays), but I figure that if I convince one stubborn vim user to switch to neovim, I’ve done a great service. ↩︎

Which was in a leetcode problem, of course. ↩︎

Emphasis on you (you have to use them, not watch somebody else use them). This means that the following explanation might not be too helpful, but I’ll include it anyway, because it demonstrates thoughts that I had that helped in my understanding. ↩︎

We can’t because

&dyn Sampleableexposes no method for cloning. ↩︎Obviously I wouldn’t do anything especially esoteric in Rust, like overly general typeclasses (like

Monad) or currying. My point is that Rust makes it easy to write code in a generally functional style. ↩︎This code_report video does a good job showing/explaining the difference in “feel” between Rust and the alternatives. ↩︎

You don’t have to code in Haskell too long before you’re bashing your head against the wall because you’re three monad transformers deep and you realize you need another layer of mutability. Sometimes it’s just easier and clearer to give up purity and immutability, and doing so can be relatively safe so long as it’s in a controlled environment. ↩︎

That’s not to say Rust is perfect, but rather that I (personally) like the way it does things, and that it shows great potential for how paradigms can be blended. ↩︎

According to this talk by Guy Steele, giving users power over language-level features is necessary for growing a language. ↩︎

I used the gtk-rs bindings, which are decent, but leave some things to be desired (I blame this on the C-style nature of GTK (and its clash with Rust), not the developers who wrote GTK or the bindings). ↩︎

Rust’s

include_str!()macro comes in handy for including the css file at compile-time. ↩︎“Pretty” in the eyes of my younger self (“relatively complex”). ↩︎

This is a paraphrase of the definition of “wicked problem”; this isn’t to say I wasn’t confident that I could complete it, but rather that it was sufficiently complex that its implementation couldn’t effectively be planned. There’s a certain poignancy to these problems, because solving them involves a leap of faith: the optimism of a programmer that defies logic that says “I can probably do it”, despite insufficient evidence that it actually can be done. ↩︎

I’m not just referring to wicked problems here, though; I’m appealing to the perceived impossibility of the task (especially from the eye of my younger self). ↩︎

Text! Lifeless Text! To make a living, breathing program…. Doesn’t sound like equivalent exchange to me. ↩︎